This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

As I write this a couple days after Helene raged through the Southeast, we’re one of the few homes with power in my town. Outside, hundreds of fallen trees have caused incalculable damage to homes, cars, power lines, and roads. The stop lights are dark, and most grocery store shelves sit empty. Cars line the streets as they wait to get gas from the local QT. Few restaurants are open. Even the town’s Waffle House is closed.

We don’t have WiFi or much cell service, but a couple days ago, we figured out that we could walk to a hotel which has been letting folks use their WiFi. That was where we learned of the complete devastation of the region. Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, western North Carolina, east Tennessee, and southwestern Virginia have all been devastated by hurricane Helene.

Here in Appalachia, western North Carolina in particular has been ravaged by flash floods and mudslides. And just an hour or so north of me, the city of Asheville is still only accessible via air. Entire towns have been flattened, and parts of highways have just fallen off the sides of the mountains.

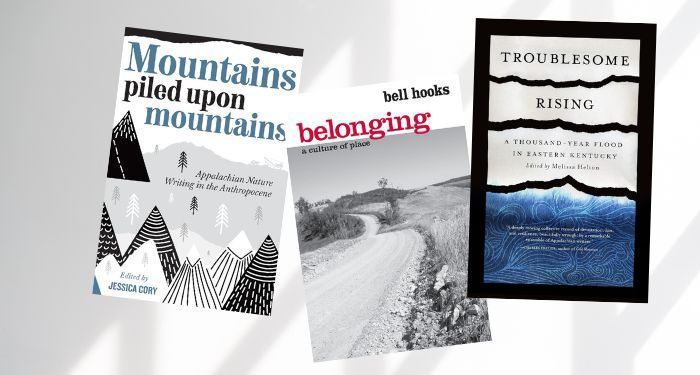

Appalachian communities have long been dealing with environmental disasters. In Troublesome Rising: A Thousand Year Flood in Eastern Kentucky, an anthology edited by Melissa Helton, writers from across the region respond to the horrific Kentucky flood in the summer of 2022. Writers like Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, Neema Avashia, and Carter Sickels write about the events of that July night when a flash flood swept through eastern Kentucky, a devastating event that the communities there still haven’t recovered from, even now over two years later.

In Mountains Piled Upon Mountains: Appalachian Nature Writing in the Anthropocene, Kathryn Stripling Byer shares a poem based on the events of a mudslide in Maggie Valley, North Carolina in 2003: “When mountainside came tumbling down / on her, where could she run? . . .Now she hears only the voice of this mountain / folding her inside its blanket of mud.” In her introduction to Mountains Piled Upon Mountains, editor Jessica Cory cites Dr. Mae Miller Claxton, who says, “Every Appalachian writer is an environmentalist.” And the contributions to Mountains Upon Mountains illustrate that reality perfectly.

Ronald Eller’s Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945 discusses more floods than I can count, many of which were caused by mountaintop removal and other harmful extractive industries. The great Appalachian flood of 1977 displaced 25,000 people. Five years before that, the Buffalo Creek disaster killed 125 people. In the chapter “The New Appalachia,” Eller details the histories of these disasters and the Appalachian people who fought for more industrial regulations so that Appalachia could have a better future.

You might ask, if these disasters are such a huge part of Appalachian history and very current present, then why do you stay? There’s no one way to answer this question. I hear it so often. But ultimately, Appalachia is our home. In Belonging: A Culture of Place, bell hooks describes how important her Kentucky upbringing was to her. Crystal Wilkinson’s culinary memoir Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks delves into her family’s deep love for eastern Kentucky, a place they have lived for generations.

We’ve just begun to fully understand the complete picture of Helene’s destruction. The prospect of rebuilding — again — feels overwhelming. Even with the disasters in our region’s past, we’ve never seen anything like this before. But I’m already seeing Appalachian people roll up their sleeves and get to work. We don’t know what recovery will look like, but we’re going to fight for it, one day at a time.

To support relief efforts, please consider donating to Operation Airdop and checking out other organizations here.