One of the joys of Substack is that it allows writers to speak to their readers in a direct and unfiltered way, one that feels and sounds a little different from a traditional newspaper op-ed or magazine article. Though my writing is still shaped by those old habits, I am trying to take better advantage of the freedom inherent in this medium, for example with my series of loosely connected observations about topics from France to artificial intelligence. In that spirit, I am today sharing my unfiltered thoughts—OK, my rant—about one of the things I most dislike about a country I love.

And yes, I know this is hardly the most important thing going on in the world right now. We’ll resume regularly scheduled programming tomorrow, with an interview with Jason Furman about tariffs, the state of the economy, and the risk of a recession.

A few days ago, an 18-year-old by the name of Zach Yadegari publicly shared his impressive accomplishments—and the disappointing outcome of his attempt to get into an elite college. Zach had a GPA of 4.0. He had a score of 34 (out of 36) on the ACT, a standardized test applicants sometimes take in lieu of the SAT. Perhaps most impressively, he is an accomplished coder who has built a genuinely successful business: an app that allows users to count calories by submitting photographs of their food, and which he claims already earns $30 million in annual recurring revenue.

Despite this impressive record, most schools weren’t interested in Zach. According to his post, he was roundly rejected by every Ivy League school (except for Dartmouth, to which he didn’t apply). Nor did he fare any better at other top colleges, such as MIT and Stanford. Even some comparatively less selective schools such as UVA and Washington University did not take any interest in him.

At first, the ensuing debate on social media focused on the disadvantages many impressive white and Asian applicants face in college admissions. After all, an anonymous hacker had recently published the latest admissions data from NYU, another school that rejected Zach, and the leak strongly suggested that many American universities are effectively defying a recent Supreme Court order to end affirmative action. The average test scores for white students admitted to NYU are lower than Zach’s; but the average test scores for Hispanic and especially black students admitted to NYU are far lower. This leaked data suggests that Zach would have been highly likely to gain admission to NYU—and perhaps many of the other schools he applied to—if he wasn’t white.

Then someone on X asked Zach to share his admissions essay, and the conversation quickly took a turn. As soon as he did, dozens or hundreds of large accounts explained to him—some in a paternalistic, others in a sneering tone—why his essay likely tanked his application. The essay was undone by “a general sense of fakeness,” one social media account with a big following judged. “For every student with perfect scores like Zach, there’s a student with near perfect scores and more humility who’s overcome terrible circumstances and does not seem entitled,” a condescending professor tweeted. “Whenever people complain about not getting in despite good grades/scores the essay is almost always garbage,” a former admissions director concluded.

Want to hear me in conversation about this strange political moment with the likes of Francis Fukuyama, Ivan Krastev and Jake Sullivan? Then check out my podcast, The Good Fight! And while you’re at it, why not sign up for ad-free access to all episodes by becoming a paying subscriber and adding a private feed to your favorite podcast app today…

And that gave me a long-awaited opportunity to pen a rant I had been saving up for a rainy day. For every aspect of this saga, from the fact that a misguided admissions essay really may have tanked Zach’s chances for admission to the way in which commentators across the political spectrum accept this exercise as a natural part of the selection process, reminds me of one of the most pernicious aspects of higher education in America.

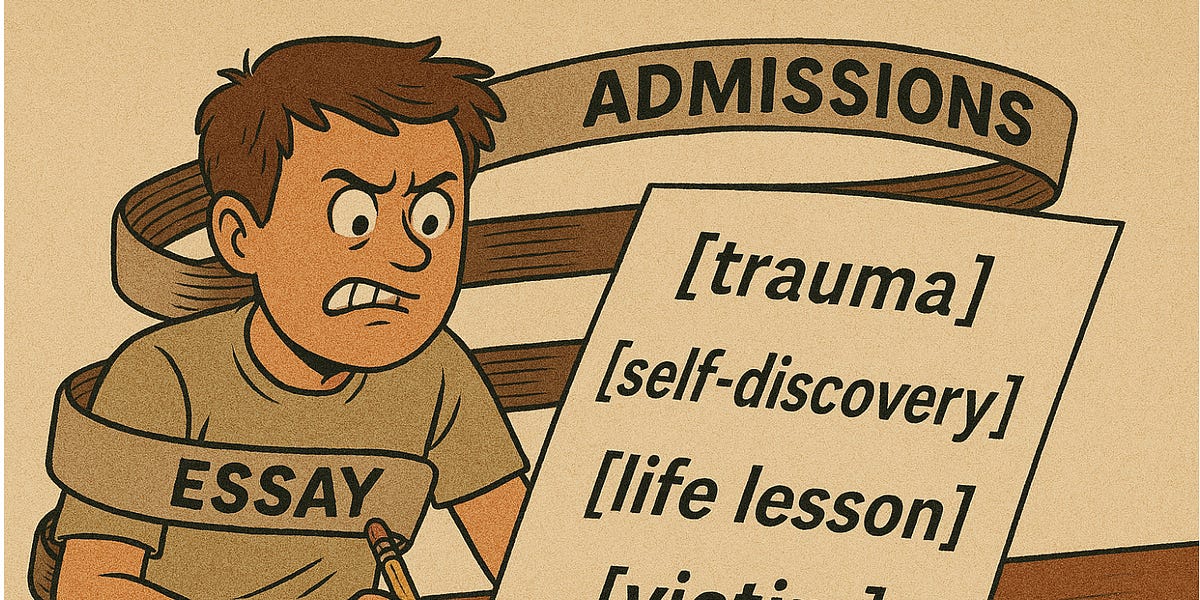

The college essay is a deeply unfair way to select students for top colleges, one that is much more biased against the poor than standardized tests. The college essay wrongly encourages students to cast themselves as victims, to exaggerate the adversity they’ve faced, and to turn genuinely upsetting experiences into the focal point of their self-understanding. The college essay, dear reader, should be banned and banished and burned to the ground.

There are many tangible, “objective” reasons to oppose making personal statements a key part of the admissions process. Perhaps the most obvious is that they have always been the easiest part of the system to game. While rich parents can hire SAT tutors they can’t sit the standardized test in the stead of their offspring; they can, however, easily write the admissions essay for their kid or hire a “college consultant” who “works with” the applicant to “improve” that essay.

Even if rich parents don’t cheat in those ways, their class position gives rich kids a huge advantage in the exercise. As the responses to Zach’s essay show, writing a good admissions essay is to a large extent an exercise in demonstrating one’s good taste—and the ability to do so has always depended on being fluent in the unspoken norms of an elite community. Legions of commentators scolded Zach for such sins as touting his accomplishments too aggressively or sounding too much like other applicants. But like avoiding the fate of the ambitious Asian immigrant parents who encourage their child to excel at the piano, only for her to be reduced to a file dismissively set aside by an admissions officer who sneers at “yet another nerdy Asian kid who plays the piano,” the ability to highlight your accomplishments in an appropriately roundabout way depends on cultural knowledge. If you come from a background in which your parents and grandparents went to college and many family friends have recently gone through the Kafkaesque process of gaining admission to an elite institution and you are friends with a person or two who teaches at such a university, then you obviously have a giant advantage.

This is all borne out by the data. Many on the left oppose standardized tests on the grounds that they have a class bias, and that hiring a tutor can make you perform better at them. But studies on the subject consistently suggest that the class bias of personal essays is far stronger than the class bias of standardized tests; notably, standardized tests can, as Rob Henderson movingly recounts in his memoir, show that kids from disadvantaged backgrounds have hidden talents to a far greater extent than college essays.

But the thing I truly hate about the college essay is not that it is part of a system that keeps deserving kids out of top colleges while rewarding privileged kids who (to add insult to injury) get to flatter themselves that they have been selected for showcasing such superior personality in their 750-word statements composed by their college consultant or ghostwritten by ChatGPT. In the end, truly talented kids like Zach are going to be just fine; he’ll still have plenty of educational opportunities at the less prestigious schools to which he was admitted, or he can keep pursuing a career in Silicon Valley without a college degree. Rather, what I truly hate about the college essay is the way in which it shapes the lives of high school students and encourages the whole elite stratum of society—including some of its most affluent, privileged and sheltered members—to conceive of themselves in terms of the hardships they have supposedly suffered.

For obvious reasons, this is especially true for members of ethnic minority groups. A big proportion of black students admitted to the most elite colleges in America are the children or grandchildren of relatively recent immigrants from countries such as Kenya and Nigeria, many of them doctors or other professionals from elite families who came to America on H-1B visas; many of the rest come from families that have been middle- or upper-middle class for multiple generations. This suggests a mismatch between the most intuitive moral justification for the affirmative action policies which colleges like NYU are evidently continuing to pursue (to provide some form of reparation for the grave ill of slavery) and the actual beneficiaries of these practices (who rarely include those from communities like Central L.A. or the South Side of Chicago, whose lives remain most obviously shaped by such historical injustices). Whatever this mismatch may imply about the moral status of affirmative action, it is the bizarre spectacle of those kids from comparatively privileged backgrounds being effectively coerced by the admissions system to self-exoticize as products of great hardship which I find to be truly unseemly.

But this game is by no means restricted to applicants from minority groups. The true art—the highest display of “good taste”—consists in transforming an applicant who is “privileged” in every dimension, including the ones particularly salient to admissions officers steeped in identity politics, into the kind of unique individual who appears to have triumphed over great adversity. Perhaps the best example of the genre I can think of is an acquaintance from college who won a prestigious fellowship to study in America based on a sob story about having his house bombed during the “troubles” in Northern Ireland; his essay left unstated that he had spent his high school years at Eton College, and that said house was one of the family’s many estates.

It’s bad enough that jostling for membership in the elite now requires ambitious Americans to turn themselves into essay-length avatars demonstrating their good taste or showcasing their resilience or performatively celebrating their quirkiness. It is worse that the prospect of having to do so now helps to shape how they spend their teenage years.

The truly ambitious kid doesn’t just sit down at the age of 16 or 17 to reflect about what element of their lives they can highlight to reveal their personality; they begin, at the age of 14 or 12 or even earlier, to lead their lives with an eye to preparing the ground for the perfect college application. (Or, worse, their parents do so for them.) This leads to all the cynical activities which pretend to showcase some intrinsic motivation but are actually covert exercises in getting ahead—witness the countless “nonprofits” now started by high schoolers on a mission to get into Yale.

The British philosopher Bernard Williams once complained that the utilitarian justification for why a man might choose to save his drowning wife rather than three similarly imperilled strangers would require him to have “one thought too many.” On the face of it, Williams pointed out, the utilitarian emphasis on maximizing the balance of happiness over pain would seem to suggest that he has to save the strangers. Utilitarian philosophers may be able to avoid this counterintuitive conclusion, for example by claiming that over the long run the balance of happiness over pain would improve if we give people some leeway to act on their special attachments. But even that, Williams insisted, wouldn’t capture the real reason why the man would and should want to save his wife: that he loves her, has vowed to protect her, and must place her interests over those of others.

Something similar holds true for the manner in which the self-marketization of college applicants transforms their attitude towards the world. Many teenagers no doubt genuinely enjoy sports or playing the violin or participating in the math Olympiad or helping little old ladies cross the street. But the admissions system makes it impossible for them not to pursue those activities with one eye to their future advancement. The central role the college essay plays in admissions forces even genuine and well-meaning kids to have “one thought too many” as they go about activities they might otherwise undertake for the pure pleasure of it. It is the first of many steps in shaping a social elite that is willing to put its own advancement ahead of any authentic engagement with the world—a social elite that has proven to be so unpopular and dysfunctional in part because those over whom it reigns smell its inauthenticity from a mile away.

And this is why I suspect that the seemingly innocuous institution of the college essay is more deeply damaging—to the high school experience, to the self-conception of millions of Americans, and even to the country’s ability to sustain a trusted elite—than it appears. The fundamental problem with it isn’t that it arbitrarily excludes some highly talented individuals like Zach from positions of power and privilege; it’s that it drains the souls of teenagers and encourages a deeply pernicious brand of fakery and breeds widespread mistrust in social elites.

The college essay is absurd and unfair and—ironically—unforgivably cringe. It’s time to put an end to its strange hold over American society, and liberate us all from its tyranny.