This week, I had the absolute pleasure of getting back to the podcast — and to Arts Journal! — by hosting a special, roundtable discussion with some of my colleagues working on the upcoming Sunday in the Park with George at Axelrod Performing Arts Center. The discussion included director/choreographer (and former guest of the pod), Eamon Foley, star (and former guest of the pod), Talia Suskauer, and co-producer of the project, yours truly! Especially because I had featured both Eamon and Talia on the podcast at different times, and because we were recording in-person, the discussion represented a really awesome opportunity to focus on a specific show/project, rather than the trajectory of any one person’s career, and, therefore, hopefully a way to keep Call Time super fresh, bold, and surprising for my listeners.

What follows is sort of part “pre-pro” (what those of us in “the biz” call pre-production work), part “table-work” (the process by which directors, choreographers, and actors sit around a “table” at the start of a production process, not unlike an English class, “Harkness table” discussion, and engage with the play dramaturgically) part lesson in how to make guerilla theatre, part casual exploration of the Sondheim canon (we end the episode with a Sondheim-themed game of “shag, marry, kill”…sorry, mom!). Because of all this, I am partial to this episode because I believe it’s a genuine, authentic “peek behind the curtain,” as it were, of the kinds of discussions creative teams, producing teams, and actors within a company are engaging at the beginning of a process.

Most importantly, Talia, Eamon, and I discuss what some see as the “essential problem” of the show. “Not that there’s a problem,” Eamon assures me several times during our discussion, quick, of course, to defend one of Sondheim and Lapine’s most treasured (and Pulitzer Prize-winning) works. Nevertheless, we can’t help but explore how many people in our orbits (Eamon’s mom, Talia’s dad, for example) can’t say they “love” the show, no matter how much they love the score, or the setting, or “act one” as a whole, because they simply don’t like George. “My dad was like, I don’t understand him, I don’t like him, I don’t understand what’s going on here,” Talia tells me about her father’s first impression of George in Sunday. “My mom was like, ‘oh, I don’t understand George’,” Eamon says, similarly. “In fact, she really slammed George. She was like, ‘he’s an idiot. He doesn’t see this wonderful woman in front of him.’”

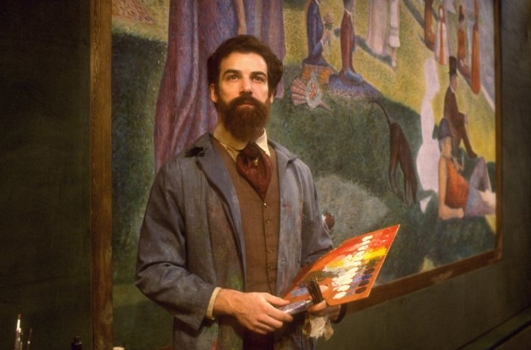

As I see it, Eamon, and this production, attempt to tackle this problem head-on through a rather groundbreaking, “dance-focused” approach. Listening to the original Broadway cast recording on his long commutes into the city as a child actor, Eamon tells me on the podcast, he saw such obvious dance in Sunday — particularly “contemporary ballet.”

Most people wouldn’t associate Sondheim with dance, especially with the kind of high-level training required to perform en pointe. In fact, I feel like most working actors joke that the Sondheim canon is pretty much the only thing keeping “good movers” employed in the musical theatre industry today! For Eamon, however, Sondheim’s lush, complex, interesting, and beautiful Sunday score demanded, nay, BEGGED for dance. “The way that this music just came to life with that pointillism element…[to me] it felt like pointe shoes hitting the floor, but it didn’t feel like Balanchine either,” Eamon explains on the podcast, “you know, it felt contemporary, but it also just required a pointe shoe. It’s just something that I knew when I was 14.”

In this way, Eamon conceptualized a production of Sunday in the Park with George where George’s mind, his artistic process, even his use color and pointillism itself were animated through contemporary ballet. This was a lightbulb moment for me, too. I had always kind of secretly felt like Talia’s dad and Eamon’s mom: “Why can’t this man get his head out of his ass and see the amazing, beautiful, vivacious woman right in front of him?” I’d find myself wondering. “Why does he feel he has to choose between his work and his personal life? And what’s so great about paint, and brush strokes on a canvas, anyway?”

This production promises that the audience will be able to SEE and FEEL what it is that George sees and feels when he creates. And this is not some kind of clever “take” on a classic show. Indeed, Eamon and I discuss on the podcast how annoyed we get with the trend of directors and producers deciding that in order to do a revival they have to create some sort of inorganic spin on the source material…Hamlet in Soviet Russia! La Boheme in space (an actual interpretation of the opera I saw in Paris)! To me, this iteration of Sunday has always felt like it’s bringing the audience even closer to the text, even closer to the themes. For maybe the first time, or perhaps in a new way, they might understand why George chooses art-making over love. They might understand why he feels all-consumed by his work. And, similarly, they might understand why Dot feels that it’s an impossible situation for her, that her leaving is inevitable, even necessary. In fact, during our “table work” discussion on the podcast, I found myself asking questions of the material I had never asked before. “Is Dot jealous of George’s ability to see and make art?” I wondered for the first time. “Does Dot wish she had what George has?”

It unlocked something in me, and my understanding of the show and the central relationship. I had always thought of Sunday in the Park with George as George’s show…I mean, he’s in the title for God’s sake! Similarly, I thought Eamon’s conceptualization would primarily benefit the audience’s understanding of George: his motivations, his inner workings, his sense of love and sacrifice. But in that moment I understood how much this physical iteration of art-making and the artistic process itself benefits our understanding of Dot. Does Dot leave, not only because she can’t play second fiddle, but also because she can’t live with the fact that she will never have what George has, never see what he sees? Indeed, I’ve always thought it would be acutely painful to be partnered with a genius, whoever and whatever gender that genius might be. How could you live with someone whose mind worked so inherently differently than yours, who was always “somewhere else”? And, furthermore, wouldn’t you start to doubt your own self, and your own self worth?

Suddenly, all the boring “wives of geniuses” plot-lines we’ve seen so often on film and television became much clearer to me. Emily Blunt’s character in Oppenheimer, Jennifer Connelly in A Beautiful Mind. Dot’s lyrics in “We Do Not Belong Together,” that I had always sort of taken at face value, suddenly became something of a battle cry. “No one is you/and no one can be/ But no one is me, George/ No one is me!” She’s not just stating facts, but crying out desperately for, demanding her own sense of self-worth and identity. “Just because I’m not an artistic genius doesn’t mean I’m not important or unique,” she seems to say. “Just because I can’t see what you see, doesn’t mean I’m not valuable.” These questions even resonate with murkier philosophical and ethical ones. Sunday in the Park begs the question: does any one person’s ability to cure cancer, or paint the Sistine Chapel, or even write a lyric like Sondheim’s lyrics, make their life more important than another’s?

The fact that all of these questions and topics of conversations can be sparked by the podcast discussion is a testament not only to Sondheim and Lapine, but also to Eamon and his artistic vision. Which leads me to perhaps our most important topic of conversation on the podcast: the way that he got this production off the ground.

As discussed above, Eamon had been imagining his take on Sunday in the Park with George since he was 14 years old. Fast forward: he graduated from Princeton with flying colors, had several Broadway shows under his belt, and still no one would really take him seriously or give him a chance. It’s why he “broke into New South” (a building on Princeton’s campus), as he tells me, in order to shoot the first of several Sondheim-inspired “music videos” that used contemporary ballet and dancers en pointe. “The idea was, ‘No one’s gonna get this unless you show it to them’,” Eamon tells me. “It just felt like: ‘you know what let’s do this.’ And with a budget of 200 bucks, and guerilla filmmaking [and] sneaking back into Princeton and setting off fire alarms…we made it.” And in fact, as Eamon tells me, that video, “Color and Light,” set off his career, got him “so many jobs,” and helped this full production come to fruition. One of Eamon’s friends was working on an opera at Axelrod Performing Arts Center out in New Jersey and showed the video to the Artistic Director…a day later, as Eamon tells it, he got the call. “We got the rights and BOOM. We were doing Sunday.”

Following which, Eamon made yet another Sunday music video, this time to the song “Finishing the Hat,” with our George, and friend of the pod, Graham Phillips. Once again, he did it because he felt like no one was going to “get it” (or give us the resources we needed) without seeing it. As I say on the podcast, it’s a quality I love and admire in Eamon. Not many musical theatre artists have the bravery, the resourcefulness, or the grit: it’s not a format that people typically associate with musical theatre. I can imagine people saying to Eamon — perhaps I even felt this way at the time — why would you shoot a music video, MTV style? Why can’t you just do things using the typical avenues: forge a relationship with a theater, get hired to direct something, and THEN put your vision onstage? Well, especially in a post-COVID environment, in which regional and Off-Broadway theaters are loathe to give someone untested and untried a chance, or even a second look, it’s my firm belief that more young, hungry artists (myself included!) need to be like Eamon. Don’t wait for the regional or Off-Broadway theater of your dreams to give you a chance: take it yourself, make the work you want to see onstage. And if it’s not perfect, or if it could benefit from a few more dollars — don’t worry; theatrical leaders with true vision will see what you see, and the audience, as well as general buzz, speaks for itself.

Listen here for my full episode with Eamon and Talia, focusing on Sunday in the Park with George. The production runs March 8-25 at Axelrod Performing Arts Center, and you will have to see it to believe it!