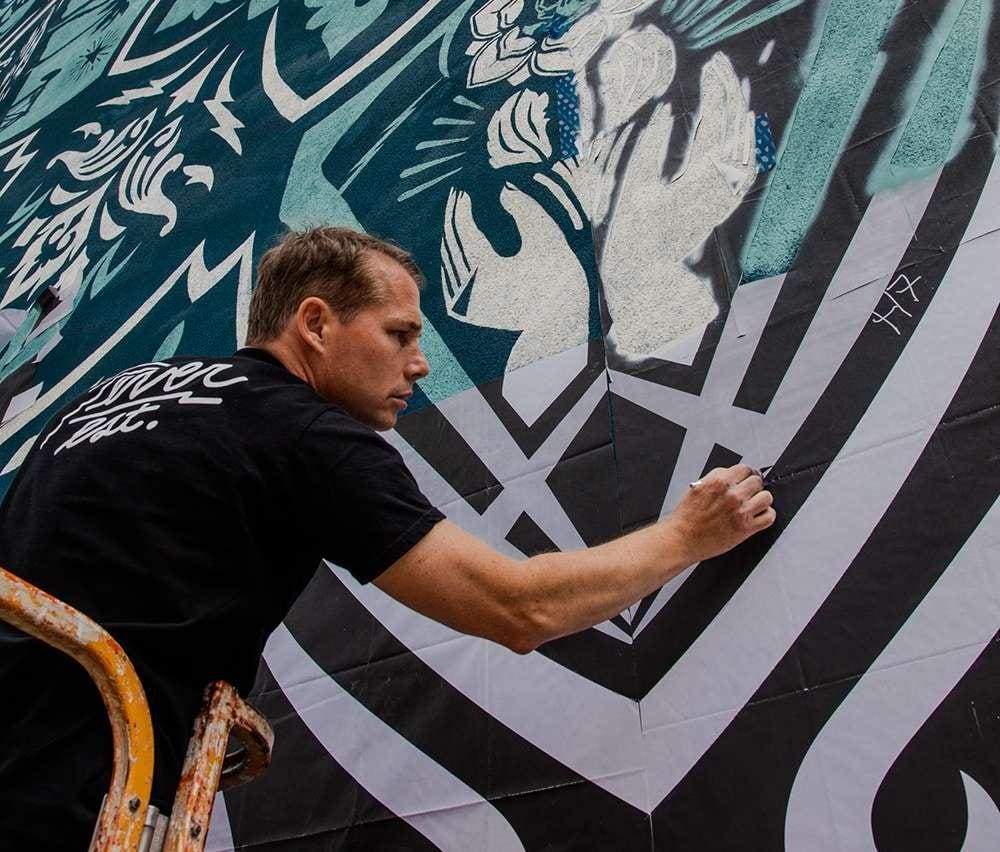

Shepard Fairey work in progress

Courtesy of Galerie Itinerrance

A groundbreaking figure in contemporary art, American artist and activist Shepard Fairey is best known for blending street art with powerful social and political messages. Originating from the skateboarding scene, Fairey gained fame in the 1990s with his “Obey Giant” campaign, featuring an image of French professional wrestler André the Giant and the enigmatic word “Obey”, which quickly became iconic on walls and streets worldwide. His work mixes elements of graffiti, propaganda, pop art, Art Nouveau, appropriation and political commentary, often critiquing consumerism, environmental issues and social justice. His 2008 “Hope” poster for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign marked a turning point, transforming a grassroots street artist into a voice recognized globally for his influence and bold style, to which he recently added the “Forward” poster for Kamala Harris’ election campaign.

Fairey shares insights about his exhibition, “We Are Here”, running until January 19, 2025 at the Petit Palais museum in Paris, which was curated by Mehdi Ben Cheikh, director of Galerie Itinerrance, and Annick Lemoine, director of the Petit Palais. The group show by major artists of the street art movement from across the globe offers an eclectic mix of works that examine themes of identity, resistance and community, challenging traditional museum norms and showcasing urban art’s depth and cultural relevance within the walls of a historic institution.

What made you agree to participate in the exhibition “We Are Here”?

Mehdi brought up the concept to me, and I said that I wanted to be involved because it’s an incredibly beautiful space and I think that a lot of art movements, when they’re new, are rejected by the art establishment, but eventually anything that connects culturally will eventually be embraced. When Impressionism was new, it was considered heresy. There was a whole upheaval about that. The same thing with abstract expressionism or pop art. Street art and graffiti have actually taken a lot longer to be finally embraced by the art establishment compared to a lot of those other movements, but I always like the idea of something that is rebellious finding a way to maintain its energy and also infiltrate the system. So I looked at that as part of the excitement of this project and also a dialog between the contemporary and the historical. I use every platform possible, including public space, of course, because that has always been important to me and is part of my history, but also I think that galleries and museums are an important way of defining what has risen to a level of importance in the art world. I think that a lot of graffiti and street art, the people who are parts of those movements, are making strong enough work to stand in a more elitist context, so they deserve to have an opportunity to exhibit in those spaces. And I think if you look at what’s being displayed at the Petit Palais, it’s the validation of that idea.

Shepard Fairey, Bliss at the Cliff’s Edge and Peace and Justice Lotus Woman, 2024, mixed media on canvas

Photo Y-Jean Mun-Delsalle

Your “Peace and Justice Lotus Woman” is very much inspired by Art Nouveau. How much has Art Nouveau inspired not just this painting, but your entire body of work?

Art Nouveau is one of many movements that I take inspiration from, but of course looking at the era that the Petit Palais was constructed, a lot of the decorative elements and architecture, it makes sense for me to have my contemporary update of the Art Nouveau influence having a conversation in the space with the original Art Nouveau. I think that a lot of people might know that my reason for embracing Art Nouveau was because it was a big influence on the late 1960’s anti-Vietnam War movement posters and a lot of the psychedelic art that was also linked to that movement, sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll and peace, so even though I feel like there are steps removed, you can also connect it right back to the source. I think that these ripple effects of an esthetic, how they end up playing out culturally, are really fascinating. My inspiration for embracing Art Nouveau was originally during the Iraq War because I considered it to be very analogous to the Vietnam War, a war that shouldn’t have happened, that the United States shouldn’t have been involved in in the ’60s, and then another one in the early 2000s. So a lot of my work commenting on peace was inspired by Art Nouveau for that reason. But I think it holds up whether you know that reference or not.

We Are Here exhibition at the Petit Palais

Photo courtesy of Petit Palais

Many of your works speak about peace like the “Peace Fingers” originally for the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, which now you’re making in response to the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Why is it so important to you to address political and social issues?

It’s a driving force in my work because I just want humans to be less brutal to each other. I guess my sense of idealism and justice is constantly looking at the horrible things we do to each other and saying, “OK, how can I convey an aspiration to do better?” That’s just part of what I think art is capable of. Art is capable of connecting with the best part of who we are as humans and stimulating the part of us that recognizes the dignity and connection with other humans. So I want as much as possible for what I’m doing with my visual art to do a lot of things that art has done for me, channeling the better part of our nature, and music does that a lot, too. I find a lot of inspiration in music that has social commentary, whether it’s aggressive music like punk rock, hip-hop, singer-songwriter things like Neil Young or Bob Dylan, Bob Marley’s reggae, Patty Smith’s poetry. I see all art forms as an important way to comment on what’s going on, so that’s just what I want to do. Not all visual artists feel the same way, but I want to try to address human problems with my art.