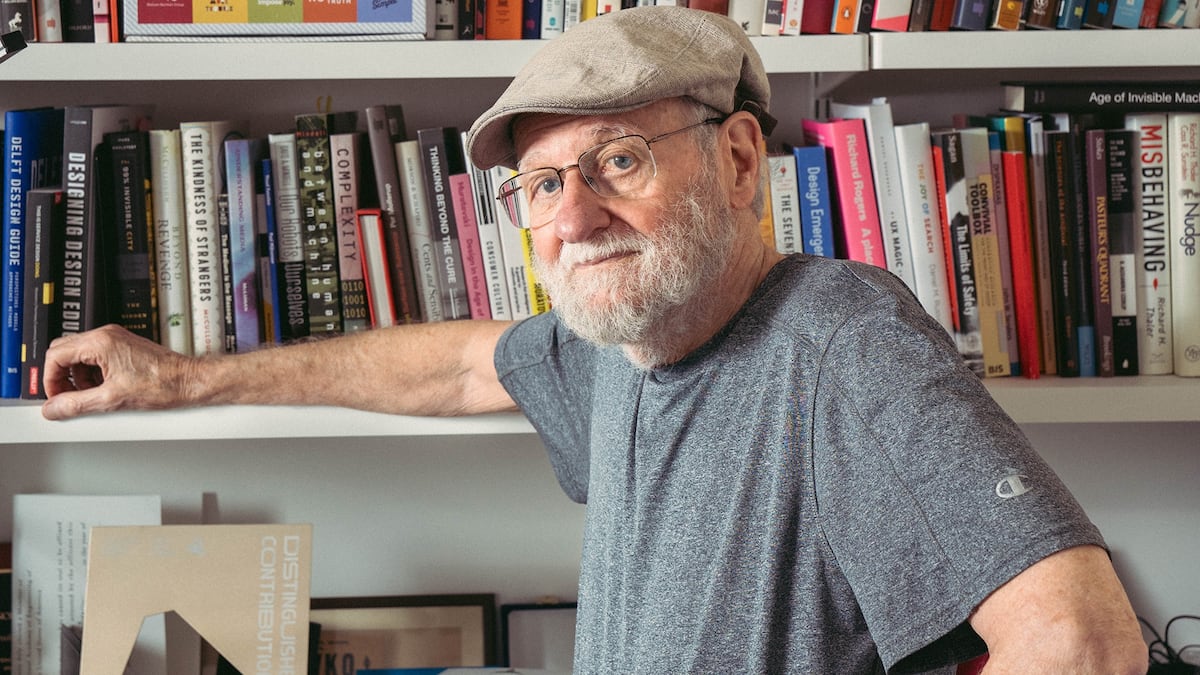

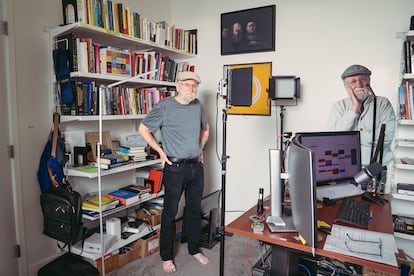

Don Norman is a man with a beard and a prophet’s frustration, a design superstar. He became an Apple vice president at a time when the company seemed destined for ruin and left when it was well on the route to becoming an empire. While he counts contributing to the design of the iPhone itself among his many achievement, today he is almost incapable of picking up one.

“Which way am I supposed to hold this device?” he growls at the vertical Zoom through which he speaks to us from his home in San Diego. “It’s almost impossible to hold it without your finger hitting the screen, and if you touch the screen, you can do something you didn’t mean to.” That something, depending on which apps one has open, might involve calling someone you don’t want to call, sending a sticker to a work chat or taking a beautiful, out-of-focus photo of the wires curled underneath the television, a passer-by’s ankle or whatever else happens to be directly in front of the phone.

“Apple computer used to be famous for the fact that you wouldn’t even need a manual. You could just pick up the telephone or plug in the computer and in seconds, you could use it and learn. It was self-explanatory,” says Norman, with the kind of fluid speech that can only come from decades of university teaching. “But unfortunately, the designers who care only about aesthetics and beauty have taken over. And I also blame the journalists who have said that the iPhone screen should be as big as possible, with no boundary [and that the center button that pre-2017 models featured should disappear]. Because when the telephone rings, I can no longer answer the phone.”

In case there was any doubt as to whether the matter was settled, Norman continues: “What happened was that Apple fell prey to the disastrous part of design, which is that design is about making something beautiful and elegant. And I say, nonsense, that’s not what my kind of design is about. My kind of design is — sure, I want it to be attractive and I want it to be nice, but more important than anything else is that I know I can use it freely and that it’s easy to learn and that it doesn’t keep changing. Apple believes that words are ugly, they try not to use them, and you have to memorize all these gestures, up and down, left and right, one finger, two fingers, three fingers, one tap, two taps, a long tap, starting from the top of screen, the middle of the screen. Who can remember that?”

Here, Norman, 88, lays bare certain essential details pertaining to his persona. He is a man with a very clear notion of the function that an object’s design must achieve, an idea so clear and so powerful that it’s practically a way of understanding the world. He likes to expound on the theory in long, astute soliloquies, the likes of which have filled hours upon hours of university classes, from Harvard to Stanford and most of the academic institutions in between.

So too have these talks figured into his career as an executive at the biggest technology manufacturers of recent decades, such as Apple and Hewlett Packard. Across five decades of this trajectory, he has become a global reference on the very specific topic of what things should look like in this world. His idea is that design should be simple. Rather than merely being beautiful, groundbreaking or new, it should be legible, manageable. Suffering for beauty is a maxim best relegated to gym workouts, stints on the operating table: objects are there to serve.

Such is the central theory of Norman’s life and of his most essential book, The Design of Everyday Things (originally published in 1988, a 2013 edition was released via Basic Books), the one that made him into a star — though, not immediately. Its original title was The Psychology of Everyday Things and it didn’t sell too well until it was renamed for the pocket version in 1990. The book also rendered him one of the most frustrated thinkers in the United States. All that fame, notoriety and influence and still, has design, in the abstract sense, improved in recent years? “I believe that design has gotten better over the years. The problem is that more things keep coming and so it gets worse and worse. But the number of good things is also increasing,” he says. “As you may know, I’m famous for doors you cannot open.”

In The Design of Everyday Things, Norman highlights the simplicity a door should embody, noting that it fundamentally presents two essential unknowns: the direction it moves and the side from which it should be operated. He argues that good design should resolve these questions intuitively, without the need for words, symbols, or the frustration of trial and error. Yet, doors that defy this logic—ones that are not immediately clear how to open—are surprisingly common. In the design world, these problematic doors are referred to as “Norman doors.”

“I’ve done so many things in my life to be famous for doors you cannot open,” he reflects.

We live in a world of Norman doors, some 36 years after the concept was coined. “What’s interesting is we know how to design well, so why do we still do that?” asks the author. “The principles of making things easy to use and easy to understand are really well-known. Yet people make fundamental, elementary errors all the time, and it’s in part because they are unaware of these principles. So that’s my frustration.”

An understandable take, and that frustration has proven quite fertile. The Design of Everyday Things has been racking up sales for nearly 35 years, edition after edition, country after country. The latest version that was published in Italy announced on its cover that it had sold one million copies.

Not everyone blindly subscribes to Norman’s philosophy, but it is impossible to locate a design professional who denies its importance. “Sometimes it’s OK for objects to be complex and have a double meaning so that our post-modern ego feels unbeatable, but in general, everyday objects should be, as [19th century designer] William Morris said, beautiful and practical. In my opinion, the beauty of utility is of the utmost sophistication,” says Jordi Labanda, illustrator and design critic. “Everyone should have Don Norman’s little book on their bedside table.”

When Norman is asked what kind of designer he is, he replies: “I design designers.”

When he was young, in the 1940s, Norman hardly attended high school and when he did, he was bored. His father worked for the U.S. Public Health Service, and the family moved continuously throughout the United States and Latin America. “I never lived anyplace for more than two years. The last place that my father was assigned to was San Salvador, but I only lived there for six months,” Norman recalls.

He eventually decided to finish out his high school career, even though the prospect proved mind-numbing. “It was too easy for me,” he says. “I was always interested in technology, and so the rest was boring.” After living the life of a nomad, he felt that he was self-governing. And he was obsessed with electronics. Those two characteristics led him to one goal: graduating.

Naturally, his eventual refuge was MIT, where in 1956, electronics had begun to be synonymous with computing. “I thought that would be easy too, because I was, of course, one of the top students always in my school. But it turned out everybody at MIT was a top student in their school. So that was my first surprise,” he remembers. He managed, at any case, to get his degree in electrical engineering and in 1960, set out for the University of Pennsylvania. There, three years prior to his arrival, they had begun to build the first computers. It was on that campus, scavenging for credits to add towards his degree, a professor made a remark that would come to define the rest of Norman’s life: “You don’t know anything about psychology.”

Norman arcs his brows in professorial acquiescence. “I was an engineer, the technical term in the United States would be ‘nerd.’ We all felt that the stuff we designed would work much better if people weren’t involved. People messed it up. I didn’t know anything about people. Even as a psychologist, I didn’t learn about people. Education at the better universities is now very specialized. You learn some very narrow thing. I have a PhD in psychology, with a specialization in how the human ear works,” he smiles. “Ask me about hearing and I can tell you, but if you want to know about people, you should talk to a novelist, a journalist. When you write a novel, you have to describe people in their life so well that the reader says, ‘Oh, I know people like that.’”

Two things came from that Ph.d, upon which Norman organized his life going forward. First, his famous distaste for specialization. “Specialists are very important, but the people who actually do things have to be generalists,” he says. He sees this as one of the world’s most dire design flaws, and having figured it out to be one of his greatest achievements. “Designers are so narrow. They’re fond of their craft skills, they’re fond of the beautiful things they make through popular design, fashion design and graphic design. But in the academic world, designers aren’t taken very seriously because they make things. I just applied what I had learned in university to design.”

The other thing was a fledgling discipline: cognitive engineering, the idea that the machine should be an extension of the human mind (which one might say is the opposite of the path now being taken by Silicon Valley). Norman is still cited to this day as one of the field’s main proponents, if not the greatest contributor to its creation. The same goes for the terms that would emerge from it: interface, user experience, usability.

Norman continued to be a nomad: he studied more psychology at Harvard, then went on to teach it himself, to begin building a reputation as the man who knew how to understand our relationship with machines. He published The Design of Everyday Things, and his niche fame began to spill out into the rest of society. He then applied his philosophy to himself. If every object must prove its own usefulness, he could not restrict his acumen to the university.

“In 1993, I left University of California, San Diego and went to Apple,” he says. “That’s when I really met designers for the first time. And I worked with a bunch of really good designers. But they were very secretive and they had their own buildings with locked doors. You couldn’t get in unless you made an appointment beforehand. Even me, when I was a vice-president!”

Norman founded and directed the first user experience group at Apple: if they couldn’t beat Microsoft in sales, at least they could make the easiest-to-understand computers in the world. One could certainly say they achieved that goal. In 1997, once again, he moved on. He started a consulting firm, returned to teaching, started other businesses. As ever, living a nomad lifestyle. U.S. Congress began to turn to him to guide the country’s technological development. How does a wifi signal travel by air? Let’s ask Norman. How many pixels per centimeter on a screen can be called “high definition”? Let’s ask Norman. The iPhone? Norman.

“Norman’s legacy in the world of design is fundamental to understanding how we have arrived at the current era. He was the one who really knew how to define the importance of design in an increasingly digital world,” says Miguel Leiro, director of the Mayrit design festival. “Amid the digital boom, Norman reminded us that what really matters is how technology integrates in people’s lives. Still, we are also witness to how his approach has spread and, in many cases, been capitalized upon, sometimes distorted in its commercial simplification. Its overexploitation runs the risk of reducing a profound methodology to a superficial tool.”

There are two books that Norman has on hand during our interview, and he frequently holds them up in front of the camera. One of them points to the weight of decades of doing what he does: remixing disciplines, stepping back to look at the whole while others see only the details, which has led him to face the ultimate failure of design, the worst example of an interface at odds with its user: humanity and Earth. In his new book, Design for a Better World (2024), he starts with a maxim from Victor Papanek, an Austrian designer: “There is no profession more evil than that of design.”

Norman explains that, “[Papanek] was correct, but he was wrong to blame designers, because they are taught the skills of design, period. But if you want to make a difference in the world, you have to go beyond your narrow skills. You have to understand culture, history, finance, how businesses work, how government works. Designers always say that their company doesn’t take them seriously, ‘They won’t listen to me.’ You have to talk the language of your customer, the people you work for. Say, here’s how many you might sell and here’s how it will change your company.”

At this point, he places in front of the camera a vintage copy of The Design of Everyday Things.

“The problem with this book is that what I teach is wrong. Now, there’s nothing wrong in the book, what’s wrong is what is not in the book. It doesn’t talk about how our designs are destroying cultures, making everyone think the Western way. The United States is guilty of that. Spain,” he says, pointing at the interviewer, “is especially guilty of that from the early years, when it conquered other countries and took over.”

He continues: “The book doesn’t talk about how we get the wonderful materials to make these light phones, how we destroy the environment by mining and manufacturing. How the current business model is that you must buy a new mobile every few years, that you can’t take them apart easily to either repair it or reuse the parts. If you were a designer and you see the company is doing that, you cannot go to your bosses and complain, ‘We’re doing it wrong.’ You have to say, ‘Here’s a way that we could still be very effective and sell products,’”

But if a man is capable of redesigning the world, does that make him a designer or a prophet?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition