A global recession, a pandemic, 9/11, the Arab Spring, Brexit, the rise of Web 2.0, unrest in the face of economic stability, wars in Afghanistan, Ukraine, Gaza, and elsewhere: these were but a few of the many events that have defined the past 25 years, a period characterized by tumult and uncertainty. That all may explain why art appeared to change faster than ever all the while, with artists burning through styles and tendencies with each coming year.

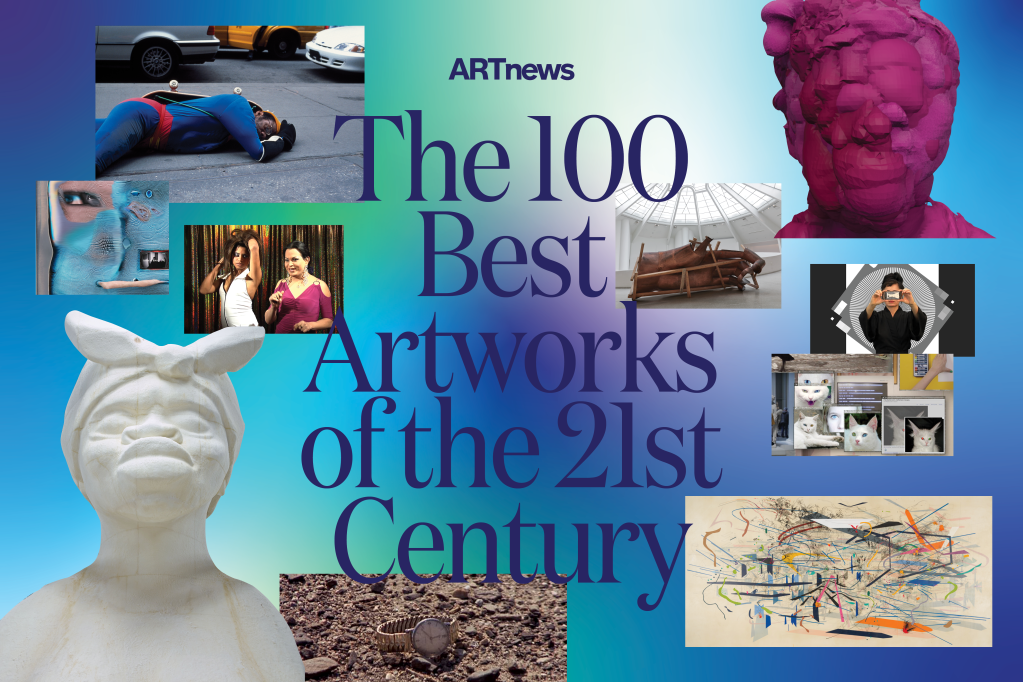

With the 21st century now at the quarter point, we’ve taken the opportunity to pinpoint the greatest artworks of the past 25 years. Even though we set down some parameters for ourselves (more on that here), it was no small task—one made more difficult by the restless creativity of artists during this period.

The joy of an epic list like this one is that it can’t encapsulate everything: we know we’ve left some artworks off, simply because there was no shortage to choose from. We hope you’ll discover some amazing pieces here, reflect on some that are much-loved already, and debate the merits of others. And moreover, we hope to learn of new artworks through the conversations we hope our list inspires.

Below, a look back at the greatest 100 artworks of the 21st century so far, as selected by the editors of ARTnews and Art in America.

This article features contributions from the following writers: Francesca Aton, Andy Battaglia, Daniel Cassady, Anne Doran, Sarah Douglas, Maximilíano Durón, Alex Greenberger, Harrison Jacobs, Tessa Solomon, and Emily Watlington.

-

Xu Bing, Tobacco Project III: 1st Class, 2011

Image Credit: Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Even from pictures, I can still feel the headache I got from this work’s pungent presence. Half a million cigarettes lean against each other to form a tiger skin carpet; walk around it, and see the colors change. By the time it premiered at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the world’s tobacco-growing capital had shifted from Virginia to China, where Xu Bing is based. Yet in Chinese branding, “Virginia Tabacco” and other romanticized references to colonial lore still abound. Xu chose the cigarette brand 1st Class because it was one of the few still grown and distributed in the United States. The work’s mass and materiality were not only stunning and stinky; the piece’s enormity gave a glimpse of global supply chains. —E.W.

-

Ken Gonzales-Day, “Erased Lynching,” 2002–

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles In the uneasy images from this series, crowds of people look up at trees or poles that seem totally unremarkable. In fact, those trees once contained something horrifying: lynched Latinx, Asian, and Native American men. These lynchings have not often been recognized in the historical record, and Ken Gonzales-Day wanted to call attention to them. Rather than reproduce the bodies of these men, however, Gonzales-Day used image editing software to remove them. The focus here, instead, is the white people who attended the lynchings, creating a public spectacle of this brutality and then circulating images of it via postcards, which the artist collected. Gonzales-Day’s jarring images force viewers to reckon with a form of collective violence that is perpetrated by regular people, frequently with little to no consequences. —M.D.

-

Anne Duk Hee Jordan, Culo de Papa, 2021

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Humboldt Forum, Berlin Before becoming an artist, Jordan worked as a diver. Underwater, she became fascinated by the symbiotic relationships shared by sea cucumbers and certain fish, who hide from predators in, of all places, the sea cucumber’s anus. Longing for such symbiosis, she turned to the potato, a German transplant much like herself, welcoming it in. First, she made a video in which she appeared to grow a potato in her own butt. Then, when the Humboldt Forum reopened in Berlin in 2021, the project got a second life. In protest of the institution, Jordan replied to the Forum’s invitation with a proposal astronomically overbudget. Home to looted objects in what was once an Imperialist palace, the Forum was occupied by Friedrich II—the king who made potatoes, native to the Andes, a German staple. Miraculously, the Forum accepted. At the grand reopening, Jordan lined the entrance with 3D-printed copies of her rump—33 of them, that butt-shaped number—all with tubers growing from her anus. This cheeky retort to nationalism and imperialism was a reminder that Germany’s treasures, even its cuisine, are extracted from elsewhere. More recently an image of Jordan’s potato-filled rump was used on posters protesting Germany’s crackdown on immigration, as if asking, will they deport kartoffel next? —E.W.

-

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite, 2012–14

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist Produced in the wake of Occupy Wall Street and a couple years after Meta (né Facebook) made facial recognition ubiquitous, Zach Blas’s Facial Weaponization Suite explores the sinister undercurrent of our surveillance state. For the work, Blas held workshops to collect the facial data of participants, and aggregated it to produce what he termed “collective masks.” Bulbous, strange, and an off-putting shade of magenta, the masks are meant not only to make users unidentifiable, but to protest the technology’s supposed objectivity. The most successful of them, Fag Face Mask, was generated with data solely from queer men in response to efforts to use the technology to determine sexual orientation, a goal obviously ripe for pseudoscience and stereotyping. Other versions respond to the targeting of immigrants and other minorities. More than a decade later, with immigrants, minorities, queer, and trans people under ever-heightening threat, perhaps it’s time to take up Blas’s call to challenge the techno-capitalist order. —H.J.

-

Dana Schutz, Frank as a Proboscis Monkey, 2002

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner As Schutz’s canvases have grown larger and her compositions more elaborate over the years, it is easy to forget the raw energy of the “Frank” paintings. An exhibition of them, at the now-defunct Zach Feuer gallery in New York, was the first time many of us encountered Schutz’s work and the punch that it packed. The show was called “Frank from Observation,” Frank being a fictional character Schutz made up; he lived on a desert island and was the last person alive. I’ve always considered the title of the show a double entendre: To paint something frankly is to paint something made of paint. Or, as David Salle has observed is Schutz’s greatest asset, “the imagining is inseparable from the paint itself.” (Or, again, as Nicole Eisenman put it more recently: “Someone like Dana Schutz is fantastic because she is painting with her eyes closed.”) This painting stands out from the other Frank paintings in the series because Frank has apparently become something else: a proboscis monkey. Is his mind so addled from isolation that he is imagining this? Is this a painting of Frank’s imagination? The mysteries have only deepened and become more complex with Schutz’s more recent canvases—which have occasionally courted controversy, as one did during the 2017 Whitney Biennial. —S.D.

-

Puppies Puppies, Barriers (Stanchions), 2017

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Trautwein Herleth, Berlin Barriers (Stanchions) comprises rows and rows of retractable belt barriers, arranged to form a maze. At the end stands a vinyl poster printed with a poignant statement borrowed from materials disseminated by the organization Immigration Equality: “FOR LGBT IMMIGRANTS, DEPORTATION CAN BE A DEATH SENTENCE. IT’S TIME FOR A NEW APPROACH.” What would such an approach entail? Surely, one that requires fewer of these seemingly innocuous barriers seen everywhere from national borders to airports, from DMV offices to museum admissions desks. —A.G.

-

Shana Moulton, Whispering Pines, 2002–10

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist Wellness often gets talked about as if it is a science: Which treatments are the best, and how do they work? This leaves out a whole lot: the feelings elicited by buying things in search of healing, and the culture that wellness has brought about. Long before Gwyneth Paltrow’s pivot to Goop girlboss, Shana Moulton created an alter ego named Cynthia who was obsessed, like Paltrow, with finding the perfect cure. Cynthia isn’t trying to sell you anything, though. In this 10-part online soap opera, absurdist videos show Cynthia chasing the high of trying something new. She does so with a wink and a nod—and also with earnest hope, something that distances Whispering Pines from the woman-hating found in many critiques of wellness culture. Moulton’s series was pivotal in steering feminist art’s conversations about bodily difference toward the realm of disability, making space for ailments as a subject in art. —E.W.

-

New Red Order, Give It Back, 2023

Image Credit: Photo Cesarin Mateo/Courtesy Creative Time New Red Order, a public secret society founded in 2016 that comprises artists Jackson Polys, Adam Khalil, and Zack Khalil, along with their collaborators, has slyly critiqued settler colonialism via installation art that calls for greater recognition than simple land acknowledgments. The group’s film Give It Back focuses on the Land Back movement, which seeks the return of ancestral lands to Indigenous people. The film features testimonials about white people who have given their land back, but this is no documentary. Jim Fletcher, a white actor who has played Indigenous characters, is shown here giving an MTV Cribs-style tour of the Upper East Side apartment that houses the Gochman Family Collection, which focuses on Indigenous contemporary art. Fletcher then uses the New Red Order film as a platform to recruit others to the cause. This is a classic New Red Order gag in which irony and seriousness combine, confusing any potential allies. As usual, New Red Order gets the last laugh. —M.D.

-

Aleksandra Domanović, Turbo Sculpture, 2010–13

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles This video was a case of right place, right time. As serious conversations about the presence of Confederate monuments in American cities were gaining momentum, the Serbian artist made this essay film about monuments cropping up in the Western Balkans after the Yugoslav wars. These statues offered a means to remember histories without heroes: The artist dubbed them “turbo sculptures,” drawing on turbo-folk, a musical genre that emerged in the former Yugoslavia, combining folk tunes with techno. The video introduces bizarre statues of Bruce Lee in Bosnia, then Rocky Balboa and Johnny Depp in Serbia, asking whether these pop icons represented a healthy rejection of nationalism, or just denial in the wake of ethnic wars. Turbo sculpture’s absurdism was not unlike that proffered by other Eastern European artists who were introduced chaotically to capitalism’s dizzying variety. Last year, for her Kunsthalle Vienna retrospective, Domanović updated the work to account for the citizen toppling of the Bruce Lee statue, a reminder that nothing is permanent, neither humor nor history, no matter how sturdily sculpted. —E.W.

-

Wafaa Bilal, Dog or Iraqi, 2008

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist The US military’s Iraq War–era insistence that waterboarding was not “torture” defied credulity. Bilal made a proposition to test the claim. Online, the Iraqi artist created a poll, asking the world to vote: Should he waterboard a dog or himself? If waterboarding wasn’t torture, after all, it should be no big deal to enlist others—or was it only no big deal when Iraqis were the recipients? Bilal “won” the poll after PETA stepped in (fair enough, considering the artist was the only consenting party). On video, he covered his face in cloth before pouring water over it in a process that simulates drowning. At the end of the video, Bilal, choking, says that “anyone who said it’s not torture should try it.” Here as ever, he puts his skin in the game in solidarity with the many other bodies on the line. —E.W.

-

Urs Fischer, Nach Jugendstiel kam Roccoko, 2006

Image Credit: Photo Rick Gardner/©Urs Fischer/Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York This brilliant artwork correctly diagnosed the art fair as a site for entertainment: Visitors pay their $30 admission and expect something big and shiny in return, and so, we got Jeff Koons’s diamond rings and hanging hearts and balloon dogs to gawk at—what critic Ben Davis called “bling conceptualism,” exemplified by Terence Koh redoing a Sol Lewitt in gold leaf and bronze (along with a gold leaf and bronze pile of dog poop). When you strolled past the booth of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise at Art Basel Miami Beach 2006 and saw nothing but a crumpled-up cigarette pack on the floor, you felt swindled. But if you stood there for a moment and waited, the thing, attached by transparent fishing line to an unseen mechanism in the ceiling, started dancing around. It is still one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen, a real fuck-you to the whole system. —S.D.

-

Laura Aguilar, Grounded #111, 2006

Image Credit: Courtesy Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016 In the mid-’90s, Laura Aguilar began a body of work in which she photographed herself and others in the nude, in a variety of landscapes. “Grounded,” her final series and the only one she ever did in color, was photographed in the rugged desert landscape of Joshua Tree National Park. These images are most impactful when they verge on abstraction. In Grounded #111, we see her nude body from behind in front of a much larger beige rock. She is seated on the ground, her back curving as she leans forward, and it takes a second to register that her body is indeed a body at all. The majesty of this natural landscape now includes Aguilar, and that was exactly her point: She wanted viewers to confront her nude fat body and appreciate it in the same way one might contemplate a desert. In doing so, Aguilar forced viewers to confront their own standards of beauty. —M.D.

-

David L. Johnson, “Loiter,” 2020–

Image Credit: Courtesy Palais de Tokyo and Theta, New York Growing up in Manhattan—specifically, Chelsea—Johnson has witnessed the increasing privatization of urban space firsthand. “Loiter” began when he noticed a certain form this phenomenon took: those medieval-looking spiked-metal contraptions affixed to standpipes, installed to prevent people from sitting on them as benches have become increasingly rare. To draw attention to this form of privatization, and to intervene in it, Johnson began removing the spikes from public areas, displaying them in galleries. This made the standpipes potential seating once again and produced new sculptures too. The effect is critique and repair together: not just a found object with a dark story, but one whose displacement is a victory. —E.W.

-

Tino Sehgal, This Is So Contemporary!, 2004–05

Image Credit: Photo Felix Hörhager/picture alliance via Getty Images During the 2005 Venice Biennale, Frieze magazine sent out SMS messages with hints as to what you would see in the national pavilions. The one for Germany was especially cryptic: The display was said to be “so contemporary.” This was the first time many encountered—“encounter” being the operative word—the work of Tino Sehgal, whose performers were seen dancing around you as soon as you made your way into the building. “This is so contemporary, contemporary, contemporary!” they sang. Sehgal had by then become known among curators as one of the primary figures associated with relational aesthetics, a tendency in which artists offered conversations and interactions, not objects, as artworks. A fair number of such works were whimsical and moving: Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1990s meals-as-art come to mind. But This Is So Contemporary! was relational aesthetics at its most charming. —S.D.

-

Aziz Hazara, “Coming Home,” 2020–

Image Credit: Photo Marjorie Brunet Plaza/Courtes the artist and Exprimenter, Kolkata/Bombay When President Joe Biden ended the war in Afghanistan, he did so abruptly: US troops left overnight with no real plan in place for an Afghan future. Predictably, the Taliban took over the next day. In their scramble, the troops left behind a bunch of trash: Gatorade bottles, junk food bags, tires, jugs. Hazara kindly collected all that garbage, effectively cleaning up the mess the Americans left behind for a gesture he has referred to as “a gift to the American people.” Then, he assembled it all into various installations that have traveled to Melbourne, Milan, Bombay, Kolkata, Sharjah, and Berlin. Next fall, at SculptureCenter in New York, the trash will return home, in a pointed provocation ultimately made of flimsy, powerless stuff. —E.W.

-

Santiago Yahuarcani, El mundo del agua, 2024

Image Credit: Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia Santiago Yahuarcani was one of the standouts of a 2024 Venice Biennale that celebrated the vastness and underacknowledged variety of the world, and El mundo del agua (The world of the water) is one of the paintings that broadcast his spirited engagement with Indigenous histories and allegiance to the land. As a member of the Aimeni (White Heron) clan of the Uitoto Nation of northern Amazonia, Yahuarcani channels stories of cosmological creatures, colonial conflict, and ancestral legacies, often on llanchama (a type of parchment made from bark). In El mundo del agua, mermaids rise, snakes writhe, and a marine organism smokes a pipe—all with a sense of intricacy and electricity that make it seem ancient and contemporary at once. —A.B.

-

Isa Genzken, Fuck the Bauhaus #4, 2000

Image Credit: ©VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/ARS, New York Though her output has encompassed a dizzying range of mediums, German artist Isa Genzken is best known for her sculpture, from fabricated pieces such as her lacquered-wood “Ellipsoids” of the 1970s and architectonic cast-concrete pieces of the late 1980s to her mixed-media assemblages of the 1990s (which, being in step with the work of younger American artists like Rachel Harrison and Jessica Stockholder, brought her increased visibility in the United States). Despite shifts in modes and materials, a consistent theme in Genzken’s art has been a fascination with modernist design and architecture, particularly their interaction with the messy business of urban life. First shown at New York’s AC Project Room in 2000, “Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York)”—a group of six sculptures pieced together from scraps of found cardboard, foam core, plastic, and glass—epitomize the irreverent yet formally sophisticated approach that has marked Genzken’s art for half a century. —A.D.

-

Precious Okoyomon, Resistance is an atmospheric condition, 2020

Image Credit: Diana Pfammatter Kudzu, a fast-growing plant that the American government brought from Japan to the US in 1876, is an invasive species that is difficult to contain. In this installation, however, kudzu is something to behold, a species that fascinates because of its unwillingness to be hemmed in. Taking the work’s title from a Fred Moten essay, Precious Okoyomon intended the kudzu as a parallel for Blackness, given the plant’s history as a means of fighting the lingering environmental effects of cotton production in the American South. Fittingly, the artist has described both kudzu and Blackness as being “indispensable to and irreconcilable with Western civilization.” —A.G.

-

Guerrilla Girls, 3 WAYS TO WRITE A MUSEUM WALL LABEL WHEN THE ARTIST IS A SEXUAL PREDATOR, 2018

Image Credit: Courtesy the artists Four decades ago, the Guerilla Girls made a name for themselves by provocatively calling attention to the disparities faced by women artists within museums and galleries. In 2018 they returned with an incisive rumination on how the art world handles allegations of sexual harassment and assault against artists—straight white males in particular—in the wake of the #MeToo movement. For this work, the Guerrilla Girls took on the case of artist Chuck Close, who the previous year had been accused of sexual harassment by women who had modeled for him. They presented three versions of a museum wall label for the artist’s 1992 portrait of Bill Clinton: one for museums “afraid of alienating billionaire trustees,” one for “conflicted” museums, and one for “museums who need help from the Guerrilla Girls.” The final text is the only one to mention the allegations; it ends with “the art world tolerates abuse because it believes art is above it all, and rules don’t apply to ‘genius’ white male artists. WRONG!” The work reminds viewers that even something as simple and didactic as a museum label is never objective. —M.D.

-

Annie Pootoogook, Man Abusing His Partner, 2002

Image Credit: John and Joyce Price Collection/Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto The community of Kinngait (known as Cape Dorset until 2020) in Nunavut, northern Canada, has produced such renowned Inuit artists as Kananginak Pootoogook, Pitseolak Ashoona, and Kenojuak Ashevak, largely through the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, an art studio established in 1959. Until late in the 20th century, works from this cooperative tended toward subjects such as birds, fish, and other animals, as well as idealized scenes of traditional Inuit life. Both Ashoona, Annie Pootoogook’s grandmother, and Napachie Pootoogook, her mother, however, were among the first Inuit artists to create autobiographical artworks. Following their example, Pootoogook likewise based her drawings on personal experience, including her struggles with addiction and—as here—abusive relationships. Her work found fame in the larger world (it was included in Documenta 12 in 2007), but the artist drowned in Ottawa’s Rideau River in 2016 at age 47. Whether an accident, suicide, or murder, her death remains a mystery. —A.D.

-

Tishan Hsu, data-screen-skin.blue, 2023

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong/©Tishan Hsu/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkPhoto Stephen Faught The imminent has at last caught up with Tishan Hsu, whose work since the 1980s has imagined how digital technologies might transform our visual world, our consciousness, and even our bodies. The pieces Hsu made while a denizen of the 1980s East Village art scene comported with the quasi-minimalist sculptures of the time, but they differed from those by, say, Ashley Bickerton or Haim Steinbach in that they pondered a data-driven future rather than a commodity-oriented present. As Hsu told art critic Martha Schwendener in 2021, “All of my work is really an effort to come up with something that would convey this paradigm that I felt would become very influential, that would have a huge impact on our reality, and that I was already seeing [happen] in much simpler ways.” By the 1990s Hsu was using emerging software like Photoshop to create silk-screened works with photo-based imagery. Since then, rapid advances in computer imaging have afforded the artist the tools he needed to produce hybrid pieces like this one, which combines references to bodies (photos of eyes and flesh-colored silicone protuberances); a screenshot of a quotidian exchange between a user and a program; and an enveloping, vaguely reptilian digital “skin.” —A.D.

-

DIS, DISImages, 2013

Image Credit: Courtesy disimages Perhaps you want to license a digital photograph of a nubile young woman bent over an open dishwasher and smelling a freshly laundered flip-flop? You can do so, for only $200, via DISimages, a library of stock photography that enlisted artists such as Katja Novitskova, Dora Budor, and Anicka Yi to produce the hundreds of images hosted on a website that effectively offers the same services as iStock and Shutterstock. The photographs DIS sold here appropriate the sleek brightly lit aesthetic of stock pictures, except that here, all the subject matter appears dark and downright bizarre. Was DISimages an ironic stunt, a ploy for attention? Not even the collective’s members could agree. But when DISimages went viral on social media, it laid bare an online appetite for meaninglessness, with a side of absurdist humor. —A.G.

-

Hamishi Farah, Representation of Arlo, 2018

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist, Maxwell Graham, New York, and Arcadia Missa, London Debates about who is allowed to represent whom lit the internet on fire when Dana Schutz showed a painting of Emmett Till, a Black teenager abducted and lynched by a white mob, at the 2017 Whitney Biennial. In one particularly controversial remark, Schutz defended herself, saying, “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America. But I do know what it is like to be a mother.” Hamishi Farah extended her logic, painting a blond child Farah claimed was Schutz’s son, Arlo, an image of whom he had found online. In so doing, Farah asked how it feels to have one’s child painted into a political debate. —A.G.

-

Sophie Calle, Impossible to Catch Death, 2007

Image Credit: ©2025 Sophie Calle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York In this 11-minute film, one of the most intimate artworks I’ve ever seen, we watch Sophie Calle’s mother’s final moments. At first, the French artist hadn’t meant for the video to be art at all; she had simply left a camera rolling in her mother’s final days, hoping to stay connected when she had to step out and run errands. But then she noticed something profound she thought was worth sharing: though in the footage you are watching someone die, death itself is impossible to see. In the video, Calle’s mother is shown lying still in bed, and after she dies, she simply lies still some more—this is a moving image that doesn’t move. Here, Calle managed to show me something I’d truly never seen before, even though it happens every day. —E.W.

-

Amar Kanwar, A Night of Prophecy, 2002

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery After the curator Okwui Enwezor stumbled upon a screening in India by the history-major-turned-filmmaker Amar Kanwar, he liked the film he saw—A Season Outside (1997)—so much that he commissioned a sequel. The follow-up, A Night of Prophecy (2002), premiered in Documenta 11, Enwezor’s defining exhibition that ushered in contemporary art’s so called “global turn.” In this feature film, Kanwar records vernacular poetry—sayings people share—derived from times of conflict, spanning eleven languages from across India. In one memorable line, a young Dalit boy asks his mother whether he is Hindu or Muslim. She replies with a searing line borrowed from a 1970s Prakash Jadhav poem—one likely passed down orally, as few Dalits then had access to literacy education—telling him, “You are an abandoned spark of the world’s lusty fires.” A Night of Prophecy implies that history is recorded not through timelines or forensics so much as the traces of poetry that they leave behind, the stories those most affected pass down. —E.W.

-

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, The Brad Johnson Tape, X – On Subjugation, 2017

Image Credit: ©Tiona Nekkia McClodden/Courtesy the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York A multitude of artists mined archives of all kinds during the 21st century, re-presenting information about under-examined histories in unexpected ways. Tiona Nekkia McClodden exemplified the trend with her multipart “Brad Johnson Project,” examining the archive of the Black American queer poet Brad Johnson, who died in 2011. In a series of 10 videos, McClodden recites Johnson’s works; the final entry shows her hanging upside-down as she reads his 1988 poem “On Subjugation,” as a way to make visceral the subjugation Johnson describes. For the installation version of this work, McClodden places a screen showing the video behind the structure from which she was suspended; that structure is itself hung with her boots and accompanied by a smattering of earth, rose petals, and naval and leather/BDSM paraphernalia. Taken together, these objects give us a fuller sense of Johnson and the life he lived. In looking to queer ancestors of the past and filling in the gaps, McClodden was able to make something wholly new, moving, and poignant. —M.D.

-

Christopher Williams, Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide © 1968 Eastman Kodak Company, 1968 (Meiko laughing), Vancouver, B.C., April 6, 2005, 2005

Image Credit: ©Christopher Williams/Courtesy David Zwirner and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne Why does the woman in this picture look so familiar? Because she’s meant to. Conceptual artist Christopher Williams’s work, usually produced by professional studios, often mimics 20th-century commercial, ethnographic, or architectural photographs. While deconstructing how such photographs continue to shape our present late-late-capitalist reality, the artist also deconstructs how they were made—here, by including a usually hidden Kodak tool. The photo’s subject is a model Williams chose using the criteria given in a casting call for Jacques Tati’s 1967 film Playtime. Her pose, open-mouthed smile, and towel-wrapped hair vividly recall bath soap ads of the 1960s and ’70s. In another nod to Kodak, the towel is the exact shade of the company’s signature yellow packaging. Despite, or perhaps because of, such extreme deliberation, the resulting artwork is as seductive as the advertisements that inspired it. —A.D.

-

Mika Rottenberg, NoNoseKnows, 2015

Image Credit: Photo Dario Lasagni/Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Informed by a visit to a pearl-making facility in China in 2014, this video captures the delicate and repetitive tasks Mika Rottenberg witnessed—in particular, the extracting and sorting of pearls. In her absurdist take on the subject, Rottenberg links these activities with a range of other seemingly unconnected ones: an administrative worker rings a bell that prompts a Chinese factory worker to turn a handle, powering a fan that then blows pollen from a bouquet of flowers into her nose. The sneezes that result mimic the way that oysters, when irritated by grains of sand, eventually produce pearls. But you don’t need to know that Rottenberg’s strange fictions are in fact based in truth for this video, which highlights the global economy’s various forms of exploitation and production that ultimately give way to the treasures we call our own. —F.A.

-

Pierre Huyghe, After ALife Ahead, 2017

Image Credit: ©Pierre Huyghe/Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery Like many of the most memorable creations by the perennially probing and prescient Pierre Huyghe, After ALife Ahead became all the more identifiable as a work by Huyghe when it started to stray from the control of the artist himself. He created this work—a “time-based bio-technical system,” as he called it—for the 2017 edition of Skulptur Projekte Münster, where it took the form of a sort of excavation of a former ice rink that was transformed into an alternately earthy and technology-abetted biosphere, with materials including bacteria, algae, bees, human cancer cells, and phreatic water (water from below the water table), along with a variety of snail whose patterned shell provided information that triggered sound- and color-changing aquarium glass. Altogether it was a kind of tribute to old and new life forces that are stranger than science-fiction. —A.B.

-

Ai Weiwei, Straight, 2008–12

Image Credit: ©Ai Weiwei Studio/Courtesy Lisson Gallery It would be easy, in 2025, as Ai Weiwei produces countless LEGO re-creations of art history, to forget just how revolutionary the Chinese artist-activist’s work has been. Travel back to 2008, however, and Ai was in a very different place in his career. That year, a devastating earthquake hit China’s Sichuan province, killing nearly 90,000 people. It was a national tragedy made more devastating by the government’s censorship of information about it. No one truly knew the scope—no one outside the immediate area, that is—until Ai created “a citizen investigation team” to interview survivors, uncovering widespread corruption in building construction, which was to blame for many of the deaths. That effort resulted in Straight. For the installation, Ai and his team collected 200 tons of mangled rebar rods from schools that had collapsed and meticulously straightened them by hand. The rods were then laid out to resemble tectonic plates in a gallery where the names of 5,000 schoolchildren who had died in the quake were displayed on the walls. A tribute to those lost, the installation is a crushing emotional experience to walk through. And, as Ai recalled in 2018, Straight and his other works around the earthquake made him “the most dangerous person in China.” —H.J.

-

Zanele Muholi, Xana Nyilenda, Newtown, Johannesburg, 2011

Image Credit: ©Zanele Muholi/Courtesy Yancey Richardson, New York South African photographer Zanele Muholi, whose work was the subject of a recent retrospective at Tate Modern, prefers to be known as a visual activist. Born in 1972, they began studying at photojournalist David Goldblatt’s famed Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg in 2001. The following year, they began photographing members of South Africa’s LGBTQI community, individuals whose rights are constitutionally protected but who are nevertheless frequent victims of discrimination, harassment, and sexual and physical violence. In the series of portraits “Faces and Phases” (2006–14), from which this photograph is taken, Muholi focused largely on Black South African lesbians and trans men, a population with which the artist most identifies. While Muholi has since expanded into theatrical self-portraits and color images of LGBTQI people in public places, these tender black-and-white depictions, which insist on the humanity of their subjects, remain some of Muholi’s most poignant images. —A.D.

-

rafa esparza, tierra, 2016

Image Credit: Courtesy Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles For nearly a decade now, rafa esparza has transformed institutions with installations made of adobe. His installation tierra, made for the 2016 edition of the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A. biennial, was among the first of these high-profile interventions, covering the museum’s north terrace with adobe bricks that were produced using dirt from Elysian Park, the site of Dodgers Stadium, which had once been a vibrant Chicano community known as Chavez Ravine. At the Hammer, esparza installed found objects in his adobe brick road, including a mailbox and a blue armchair accompanied by a cactus. Such interventions, esparza has said, stem from his “interest in browning the white cube” as a “response to entering traditional art spaces and not seeing myself reflected.” A vital part of this project has been enlisting members of his community in his art: He learned to make adobe bricks from his father, and for this iteration, he brought on his mother and siblings to help out. —M.D.

-

Luc Tuymans, The Secretary of State, 2005

Image Credit: ©Luc Tuymans/Courtesy Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp, and David Zwirner When Luc Tuymans debuted this painting in the aughts, it seemed that the world had little use for more images of Condoleezza Rice. Then National Security Advisor to President George W. Bush, she was responsible for controversially authorizing waterboarding in the so-called “war on terror” while advocating for the invasion of Iraq, falsely claiming the nation possessed weapons of mass destruction. But the Belgian artist’s portrait and its attendant commentary would prove more relevant still. Tuymans was inspired to paint Rice after her 2005 trip to Belgium, when the nation’s foreign affairs minister called her a “strong, not unpretty woman.” Her neck and chin are cropped out, and her brow is furrowed. The painting’s sickly grays and muted beiges offer a decidedly unheroic vision of this high-ranking politician, neatly encapsulating the distrust of authority that was in the air post-9/11 in the US and beyond, and turning the power dynamics of portraiture on its head. —A.G.

-

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Earshot, 2016

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Portikus, Frankfurt In 2014 Israeli soldiers in the occupied West Bank shot and killed two unarmed teenagers, Nadeem Nawara and Mohammad Abu Daher. The case hinged at the time on whether the soldiers used rubber bullets, as they claimed, or illegally fired live rounds. Together with Forensic Architecture, the London-based research group that investigates armed conflicts, Lawrence Abu Hamdan performed an acoustic analysis of the gunshots, audio of which was captured and disseminated widely alongside video of the incident. Israel initially claimed that its soldiers could not have killed the two teens, but Abu Hamdan’s research suggested otherwise: The soldiers, he ultimately proved, had fired live rounds. A year or so later, he reimagined the body of evidence as Earshot, an installation comprising photographs, video, and audio. The gallery thus became another court of culpability. Here, art functioned as journalism should, with the power to hold politics accountable to fact. —T.S.

-

JODI, My%Desktop, 2002

Image Credit: Photo John Wronn/Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York During the late ’90s, Apple’s Macintosh computer touted a sleek aesthetic, distinct from the less user-friendly PC. That’s why, for this “desktop performance,” as the artists call it, the Dutch duo JODI—Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans—used a Mac to induce a dizzying experience, one at odds with Apple’s claims of seamlessness. Using an OS 9 operating system, JODI opened up folders within folders, files upon files, until it all climaxed into chaos. Hosted as an interactive work on JODI’s website and later recorded via screen capture, the piece required its user to close out of an overwhelming barrage of windows, putting Apple’s marketing to the stress test. With My%Desktop, one of the defining works of net art, JODI shows how Apple streamlined, and perhaps even sanitized, the act of computing, alluding to how the corporation tried to obscure computational processes. —A.G.

-

Wangechi Mutu, Yo Mama, 2003

Image Credit: Digital Image ©Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York Wangechi Mutu had in mind a specific mother while creating this collage: Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti, whose son was the pioneering Nigerian musician Fela Kuti. Yet the woman shown here is just as easily a stand-in for many more women, specifically “all the mothers who give us our voices and empower us to be who we are and believe in our talents,” as Mutu put it in an interview published alongside her 2023 New Museum retrospective. Her subject is shown sinking a stiletto into the neck of a severed serpent, a “monster that managed to span two … continents,” per Mutu, who has also said that the work shows opposites colliding: “African/European, archaic/modern, religion/pornography.” The result is a fantastical world filled with disco balls and gigantic jellyfish, with implicit critiques, unglued from reality, laying the ground for a whole new world. —A.G.

-

Pipilotti Rist, Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters), 2008

Image Credit: Photo Frederick Charles/©Pipilotti Rist/Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine This installation was a progenitor of the blockbuster immersive video boom that critics love to hate. Indeed, it got the kinds of criticism such videos get today: that it was too pretty, that it was merely spectacle. When it debuted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Jerry Saltz wrote that the piece served as but a backdrop while visitors typed on laptops or hung out. In protest of the video’s lulling, hypnotic appeal, another artist even staged a yoga class inside MoMA. But beneath the piece’s consumable veneer, Rist sneaked in something subversive: this sleepy, gorgeous film is about menstrual blood. In it, Rist’s protagonist sets out to collect her menses in a silver chalice, but rendered in fuchsia instead of scarlet. Floating freely in an underwater world, her blood feels palatable, even pretty. Rist’s feat was making menstrual blood as boring and ordinary as it really is. —E.W.

-

Paul Chan, 1st

Light, 2005

Image Credit: Photo Jean Vong/Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York Paul Chan’s 1st

Lightconjures a sense of wonder by way of a sort of shadow play projected on the floor. For 14 minutes, in a state of soundlessness that grows more and more profound, the work cycles through a succession of slow-motion imagery that fluctuates between the familiar and the abstract. As if backlit by a window nowhere to be found, a series of squiggles and lines is accompanied by the silhouettes of birds flying off in the distance. Then, shortly after, the shadows of bodies begin to tumble and fall upside-down, turning the mood unmistakably somber. The presence of streetlights and railroad cars suggests an urban setting being torn asunder, and in that, 1stLightsummons memories of 9/11 that remain just as haunting now as they were when Chan debuted this work in 2005, four years after that tragic day. —A.B. -

Basel Abbas and Rouanne Abou-Rahme, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2022

Image Credit: Courtesy the artists In 2010 Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme were in Palestine, watching the Arab Spring uprisings through social media. The images of protesting, dancing, and singing that passed through the digital slipstream made them determined to counteract the amnesia of the internet. That impulse evolved into an ongoing project to document and preserve Palestinian culture against its ongoing erasure at the hands of the Israeli state. The work has taken many forms: installations, an interactive web project, public performances, and sculptures. While the ground-level urgency of May amnesia… has never been more clear following the decimation of Gaza, the work is also formally daring. By engaging a digital vernacular that blurs boundaries between artist, subject, and audience, this work refuses a frozen, historicized vision of Palestinian identity. We are still here, the work says in so many ways—still dancing, still singing, still resisting. —H.J.

-

Louise Lawler, Big, 2002/03

Image Credit: Jonathan Dorado/Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York Louise Lawler took this photograph just after Art Basel Miami Beach held its first edition. The weirdness of the fair—its rampant commercialism and fast-paced sales, both seemingly at odds with much of the conceptual art showcased there—may explain Lawler’s unusual approach to photographing Marian Goodman Gallery’s inaugural booth at this event. Here as in other works, Lawler takes aim at works by her well-known male colleagues—in this case, Maurizio Cattelan’s sculpture of Pablo Picasso and Thomas Struth’s photograph of a museum. Rather than shooting these objects straight-on, Lawler pictures them mid-install, such that the head of the Cattelan sculpture is shown separate from the body, which lies on a blanket beneath the Struth photograph. With the Cattelan sculpture represented as though decapitated, Lawler dressed down Picasso, that symbol of male genius, while also offering an unglamorized glimpse of how the sausage that is the art world gets made. —A.G.

-

Danh Vo, We the People, 2011–16

Image Credit: Cathy Carver/Courtesy Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Marian Goodman Themes of capitalism, colonialism, and immigration meet in this work, a one-to-one replica of Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty. The work’s 300 or so pieces commissioned in 2010 from a fabricator in Shanghai remain forever disassembled. Depending on how they are exhibited and where, the isolated pieces resemble welded copper abstractions, salvaged artifacts or scrap metal sold on the cheap (one piece was even reported missing in 2014). Myriad readings befit the installation, which alludes to the malleability of state symbols, particularly those purporting to represent freedom—whatever that currently means in America. “We the People is not about going to the past,” Vo said of the work on its debut. “Since it’s one of the most important icons for Western liberty I think [it] is very much about the present and our future.” —T.S.

-

Paulo Nazareth, “Noticias de América – News from the Americas,” 2011–12

Image Credit: Courtesy Mendes Wood DM For 10 months, artist Paulo Nazareth traversed the Americas, starting from his home state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, and ending in Miami, for an edition of Art Basel Miami Beach. Nazareth has described the trek, covering several thousands of miles and 15 countries, as “a residency in transit” and an “accidental residency.” Along the way, Nazareth documented what he saw in photos, videos, texts, and found objects, providing a firsthand look at how grueling the process of migrating from South America to the United States can be, both physically and geopolitically. In one image from the series, a tiny US flag lies under the artist’s bloated dirty feet; in another, he stands before a sign demarcating the Arizona state border holding a placard that reads WE HAVE RIGHTS AT THIS LANDSCAPE. In many ways, the project points to the absurdity of man-made borders, particularly when confronting the perseverance needed to navigate them. —M.D.

-

Cao Fei, RMB City, 2009

Image Credit: Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Vitamin Creative Space Second Life, a multiplayer virtual platform popular during the 2000s, beckoned users with the promise of a fresh start in an online-only world. Yet in using the platform for this piece, Cao Fei showed that digital dreams were inextricable from the IRL world. Named after the shorthand used to describe the Chinese yuan, RMB City may have seemed like an escape from 21st-century China, whose citizenry had been reshaped—and alienated—by attempts at globalization. In Cao’s alternate reality, one found a floating panda, carefully manicured fields, and a giant spinning wheel set on a sunny blue isle. But one also found the stuff of unchecked urbanization: a crane, slick yet scarcely populated skyscrapers, a smokestack belching fire. All this combined to form a landscape that was at once familiar and fantastic, showing how our fantasies are hard to cleave neatly from the worlds we know. —A.G.

-

Ed Atkins, Us Dead Talk Love, 2012

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery When this 2-channel, 37-minute piece debuted, the animation felt frighteningly cutting-edge. Over a decade on, it’s still uncanny. It’s clear now that this owes less to the technology, which is already dated, than to how Atkins uses it, blending CGI’s sleek hyperrealism with realism of a gritty variety. The computer-generated skinhead protagonist of Us Dead Talk Love has phrases tattooed on his face—they change over the video’s duration, from ASSHOLE to FML to DON’T DIE. We watch him smoking, shirtless, singing a melancholy tune with lyrics proclaiming that love makes us sad, and sadness makes us drink. Scenes show a limp dick, a man passed out at the bar, words like ENFEEBLED and DISAFFECTION hovering in cheesy fonts. It’s all chillingly affecting—its sadness too real, its presentation not real at all, the video’s sheen incongruous with its sorrow. As ever, it’s Atkins’s skillful, poetic writing that carries the piece. —E.W.

-

Wu Tsang, Wildness, 2012

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist/Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin The protagonist of Wildness is not a person but a place: the Silver Platter, a Los Angeles bar that narrates the film. Founded in the 1960s in the city’s MacArthur Park neighborhood, the Silver Platter has long offered a safe haven to LA’s queer and trans communities, as well as to immigrants from Latin America. (The bar shut down in 2010 and has since reopened under new management.) The film’s backdrop is the bar’s weekly “Wildness” party, organized by director Wu Tsang, who also stars, and DJs NGUZUNGUZU & Total Freedom. Noirish shots of the bar and its environs, weekly drag performances, and people dancing are interspersed with talking-head interviews. Amid all this is a moody narration spoken by Mariana Marroquín and drawn from oral histories by Tsang. Wildness is a portrait of both a bar and a community built by it, where “the struggle to find adequate labels/identities/descriptors for this ‘community’ is precisely what the film is about,” as Tsang once put it. —M.D.

-

Mark Bradford, Bread and Circuses, 2007

Image Credit: ©Mark Bradford/Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Posters and ephemera salvaged from the streets of Mark Bradford’s South Central Los Angeles neighborhood are layered to form the surface of this unconventional painting, which he made by sanding down its various strata, exposing fragments of information embedded between them. The result looks like a form of cartography—a map, perhaps, of a dense network found in the vast metropolis that Bradford calls home. Yet the painting is not only a celebration of South Central: Its title refers to a Roman term of appeasement used to distract the public from more substantial issues, like poverty and disenfranchisement. The work’s beautiful surface could serve as a similar kind of distraction, but his materials make clear that he’s dealing with real problems impacting his community. —F.A.

-

Cory Arcangel, Super Mario Clouds, 2002

Image Credit: ©Cory Arcangel/Courtesy Lisson Gallery We may want to imagine that nostalgia-inducing franchises from the past are set in stone. But Cory Arcangel suggested with his 2002 installation Super Mario Clouds that everything is inherently fungible. To make the work, Arcangel undertook the laborious process of hacking a Super Mario Bros. cartridge, removing every element except the game’s pixelated clouds and vibrant blue sky. Presented on monitors and projected on nearby walls simultaneously, those clouds now float on without Mario, Luigi, or their cohort to race around beneath them. From the detritus of consumerism, Arcangel forged something new: an artwork that resembled its source material in spirit alone. —A.G.

-

Maurizio Cattelan, Him, 2001

Image Credit: Leon Neal/Getty Images The sculpture represents a person with the creviced face of a 50-year-old man and the body of a grade-school boy—the contrast would be jarring enough even if it weren’t, well, him. Cattelan himself said he nearly destroyed the piece depicting Adolf Hitler after completing it, but in the end, he made it in an edition of three (a fourth copy, the artist’s proof, sold for $17 million at Christie’s in 2016). We think of Hitler as a dark cloud looming over history, but here we are able to look down on the man, who is posed as a supplicant. Cattelan called the piece “a test for our psychoses.” He completed it in early 2001; a half year later came 9/11 to prove that, pace Fukuyama, history had not ended. We live in it still. —S.D.

-

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist, 2007–

Image Credit: Courtesy Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago Some 15,000 objects—roughly half of which remain at large today—were looted from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad after the American invasion of the country in April 2003. A few years later, Michael Rakowitz set out with the goal of creating to-scale reproductions of every stolen artifact, a project so epic that it is still ongoing. Each replica is made using Middle Eastern commercial packaging for foodstuffs and local Arabic newspapers that were then exported to the US. Though these looted artifacts are now made visible once more, Rakowitz’s efforts also underscore the fragile nature of the originals, which may never return to the Museum. The piece doubles as both a form of institutional critique and a kind of research art: Accompanying labels reveal each original object’s status, and provide additional contextual information about its whereabouts from experts. —F.A.

-

Ragnar Kjartansson, The Visitors, 2012

Image Credit: Photo Petri Virtanen/Finnish National Gallery/©Ragnar Kjartansson/Courtesy Luhring Augustine, New York, and i8 Gallery, Reykjavik One way to establish intimacy with an audience is to stage an artwork that revolves around plaintively strumming a guitar while naked in a bathtub and singing a song that tugs at the heart and explodes with emotion. That is what Ragnar Kjartansson did for The Visitors, a mesmeric nine-screen video installation that features the Icelandic artist and a cast of his friends bowing, plucking, and picking their way through a cryptic piece of music whose soft spot for slyness and sentiment is clear. Though the title alludes to the name of Swedish pop group ABBA’s last album, the lyrics draw from a poem written by Ásdís Sif Gunnarsdóttir, Kjartansson’s ex-wife, with whom he had recently split. The words aren’t easy to decipher (they’re both sad and uplifting, and the breakup was said to be amicable), but they strike an improbably moving chord when they cycle back around to a much-repeated chorus: “once again I fell into my feminine ways.” —A.B.

-

Jill Magid, “The Barragán Archives,” 2013–

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Labor, Mexico City When Jill Magid was denied access to the professional archives of Mexican architect Luis Barragán—which were bought by the Swiss furniture company Vitra—she turned the problem into an opportunity, steering the genre of institutional critique away from museums and toward corporations. First, she contrived clever ways to get around copyright restrictions. Instead of paying a licensing fee to reproduce a photograph, for instance, she bought a book that had already printed it, then framed the whole book. Forbidden from re-creating his iconic pyramidal lectern, she skirted copyright law by adjusting the scale—that is, until a French show under new jurisdiction required she throw a blanket on top. Despite these persistent public pleas, archival access remained restricted. Then, Magid managed permission for something even wilder: with the consent of Barragán’s family, she exhumed his ashes and turned them into a diamond, which she then used to propose to the archive’s keeper. The offer of her proposal still stands. —E.W.

-

Paul Pfeiffer, John 3:16, 2000

Image Credit: ©Paul Pfeiffer/Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York If you needed a reminder of the sheer power of this artwork, you had a chance to see it last year during Paul Pfeiffer’s survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. I saw that show, and can report that John 3:16 has aged exceptionally well, given that, if anything, we revere sports stars even more now than we did at the turn of the millennium. On a tiny screen, a basketball appears to dart around a court in the absence of players, their hands merely hinted at. You have to get up close to see this little screen, as you would with a liturgical manuscript. (The piece is named for the famous biblical passage: “For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”) In casting basketball as revelation, Pfeiffer mined footage from the NBA, splicing together clips with the utmost meticulousness, doing for the game what Christian Marclay did for time with The Clock. —S.D.

-

The Yes Men, Untitled Bhopal Disaster Performance, 2004

Image Credit: Courtesy Yes Men After the Yes Men made DowEthics.com, a website spoofing Dow Chemicals, they received an invitation from a BBC journalist who was apparently not in on the joke. Andy Bichlbaum, a member of the art collective, gleefully accepted, appearing in front of 350 million viewers on the 20th anniversary of the 1984 Bhopal disaster that exposed hundreds of thousands of Indians to toxic gas. The artist, pretending to be a businessman, took “full responsibility” for the gas leak at a pesticide plant and issued an apology to the thousands killed and the many more rendered chronically ill. Stocks plummeted; the Dow retracted. The Yes Men highlighted the authority we bestow on white men in suits, then wielded that power against, well, power itself. —E.W.

-

Thornton Dial, Ninth Ward, 2011

Image Credit: Pitkin Studio/Art Resource, New York In the 1980s, after retiring as a machinist at the Pullman boxcar factory in Bessemer, Alabama, Thornton Dial started making assemblage sculptures and reliefs. By the time of his death in 2016 at the age of 87, he had been widely recognized as a major contemporary artist whose work—materially inventive, formally rigorous, and politically astute—rendered the distinction between trained and self-taught immaterial. In 2011 Dial embarked on a series of reliefs inspired by natural disasters, including the Tuscaloosa tornadoes of 2000 and the Japanese earthquake and tsunami of 2011. In this piece, an undulating wave of tree branches, torn metal, and scraps of sequined fabric set against a watery blue and white painted background, he memorialized the devastation Hurricane Katrina caused in New Orleans in 2005 and its disproportionate effect on the city’s largely Black Lower Ninth Ward. —A.D.

-

Steve McQueen, Static, 2009

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery When the Statue of Liberty reopened following its eight-year hiatus, the mood was tense. Though the destruction of the 9/11 attacks that prompted the closure was in the distance, the trauma of that fateful day remained present. Steve McQueen captured the spirit of this post-9/11 moment with Static, a film in which the camera circles the motionless Lady Liberty pinned to a tiny island not far from Manhattan. Shot from a helicopter, McQueen’s film takes on the perspective of the surveillance technology that became pervasive after the Twin Towers fell, but offers no direct statement on wounded national pride, and thus comes off confounding rather than clarifying. Therein lies its power: It’s a disorienting gesture for a directionless time. —A.G.

-

Jana Euler, GWF 1, 2019

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist, Galerie Neu, Berlin, and Greene Naftali, New York Jana Euler has strategically deployed ugly images, sometimes in bad taste, as a means of aesthetic assault, and though nearly every one of these efforts is a banger, her most provocative pictures are the ones in her “GWF” series (2019), in which elongated sharks leap out of the ocean. There can be no mistaking the fact that these sharks, with their ribbed gullets and raging heads, look more than a bit like erect phalli. Yet these sharks are hardly seductive: the one shown in GWF 1 flails ungracefully, bearing its teeth and gazing down at the viewer, who seems poised to become the fish’s lunch. Large for a phallus and agile for a shark, Euler’s apex predator is no object of admiration. Instead, it’s simply a dick joke. —A.G.

-

Daniel Joseph Martinez, The House America Built, 2004

Image Credit: Courtesy Orange County Museum of Art On its face, Daniel Joseph Martinez’s The House America Built seems like a simple, large-scale installation of a small cabin split in two and painted in complementary colors. But what house is this, really? That’s the point of Martinez’s inquiry: the place could belong to just about anyone, even though his reference points are highly specific to American history. The structure is a 1:1 replica of the remote cabin that Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, built and lived in, and the color palette draws from Martha Stewart’s seasonal collection of interior paints. Kaczynski and Stewart are both Polish Americans, born within a year of each other, and while they took very different paths in life, both were incarcerated in 2004, the year Martinez made the original installation. The piece presents the ends of what Martinez sees as the spectrum of Americanness: Stewart and high capitalism on one, Kaczynski and anarchy and domestic terrorism on the other. —M.D.

-

El Anatsui, Dusasa II, 2007

Image Credit: Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York El Anatsui has made an artistic practice out of stringing together thousands of metal bottle caps to form large, vibrant tapestries, and while he’s repeated the format many times over, it never gets old. Anatsui’s oeuvre reached new heights with this 24-foot-long sheet of caps, which was originally created for the central exhibition in the 2007 Venice Biennale. This work, like his others, cleverly references contemporary overconsumption in material resulting from that consumerism, and is fashioned with gentle folds in a way that recalls traditional Ghanaian craft traditions, like kente cloth. But here, more so than in other works, Anatsui also makes clear that the strung-together caps nod specifically to his own community, whose many members help him make his grandly scaled art. The title, he has said, could be translated from the Ewe to “communal patchwork made by a team of townspeople.” —F.A.

-

Josh Kline, Cost of Living (Aleyda), 2014

Image Credit: Photo Ronald Amstutz/Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Before 3D printing was widely accepted as an artistic medium, Josh Kline embraced it for this unsettling sculpture of a Manhattan hotel housekeeper named Aleyda, whom Kline interviewed and scanned. Featuring to-scale, 3D-printed versions of several of Aleyda’s body parts along with cleaning supplies arrayed on a janitor’s cart, the piece comments on how technology has forever altered the workforce. The plastic cart was purchased and will last, but the body parts and tools of her trade are disposable prototypes about which a question looms: What role will the human hand play in the future of our lives and our art? —A.G.

-

Meriem Bennani and Orian Barki, 2 Lizards, 2020

Image Credit: Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Lodovico Corsini. Brussels; and Francois Ghebaly, New York/Los Angeles Animators Meriem Bennani and Orian Barki created this series of eight short videos during the first months of the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown in New York City. The videos portray friends, strangers, and the artists themselves as digitally created avatars superimposed on real-life footage. Bennani and Barki star as the titular lizards; friends appear as a snow leopard and a hummingbird, among other creatures; and Dr. Anthony Fauci is depicted as a fanged green snake. Strangely, this approach conveys the weirdness of that time and place more effectively than if the artists had made a straightforward documentary. Moments of panic (the lizards freak out during a nighttime drive through a depopulated Brooklyn) and distress (a hospital-nurse cat recalls helping a wife put through a call to her husband, who is on a ventilator) alternate with scenes of resilience: a Zoom birthday, a stoop meet-up, an impromptu street concert. It is a piercing reminder to anyone who was in the city at that time of just how bizarre things were. —A.D.

-

Pope.L, The Great White Way: 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street, 2001–09

Image Credit: ©Estate of Pope.L/Courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York Pope.L began crawling urban streets in 1978, and though much of his work was made in the 20th century, his influence grew wider after the turn of the millennium. He was overlooked before in part because his public performances were easy to read as regular New York nonsense—and because the art world was not yet ready for his abjection, his pranks, or his Blackness. For this particular Crawl, he shimmied up the entire length of Broadway, going at it in chunks over the course of nine years. And he did so alone, on elbows and knees in a Superman suit. The cartoon-reference humor was strategic: in New York, a Black man on the ground is too likely to be ignored. Pope.L refuted this with a Superman suit that screamed: Look at me. —E.W.

-

Sondra Perry, Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation, 2016

Image Credit: Photo Edward Wong/South China Morning Post via Getty Images To experience this work by Sondra Perry, one must climb onto an upright stationary exercise bicycle, thereby experiencing a degree of discomfort. And discomfort is the point, as Perry’s digitally produced avatar, appearing on the video screen that replaces the bicycle’s control panel, demonstrates when it asks “How does your body feel inside us?” The avatar is an imperfect simulacrum of Perry: Its movements are stuttering, its voice robotic, its body thinner than the artist’s and hairless. This is not Perry’s fault, the avatar tells us, but the fault of the program that created it, which had no preexisting template for Perry’s body type. Over the course of a 9-minute video, the idea of discomfort is expanded to include the question of whether racial uplift must entail making a Black body a neutral body, a process that the avatar likens to working on an exercise machine with its pedals installed backward and no hex key. “We are not as helpful or Caucasian as we sound,” the Perry avatar says. “We have no safe mode.” —A.D.

-

Emily Jacir, Where We Come From, 2001–03

Image Credit: Photo John Sherman/©Emily Jacir In 2001 Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, who holds an American passport, asked Palestinians unable to enter to Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, as well as Palestinians in those three places whose movements are restricted, “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” For the next six months, she did her best to fulfill their requests, documenting her attempts in text and photos. One man asked her to visit his mother; another asked for a photo of his family (they gave her strawberries and lemons grown on their land to take back to him). A third asked her to pick an orange in Jericho and eat it (this, she was unable to do). About this piece, the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said wrote, “[Jacir’s] compositions slip though the nets of bureaucracies and nonnegotiable borders, time and space, in search not of grandiose dreams or clotted fantasies, but rather of humdrum objects and simple gestures like visits, hugs, watering a tree, eating a meal—the kinds of things that maybe all Palestinians will be able to do someday.” —A.D.

-

Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, Hope the Air Conditioning Is on While Facing Global Warming (part 1), 2017

Image Credit: Courtesy Reena Spaulings Fine Art and Bortolami Gallery, New York Many artists this century grappled with how painting for its own sake is seen as a Western construct, with Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s contribution being among the most articulate. In altarpiece-style works with panels on hinges, she renders her subjects in a manner that appears amateurish; she then hires family members to embroider her surfaces using a traditional Mexican technique. Here, her altarpiece format approximates the shape of a Tesla, a subject Toranzo Jaeger took on after noticing that many fellow Indigenous artists were at work to preserve history in the face of erasure. She wanted to supplement these efforts by ensuring that Indigenous imaginations had a voice in visions of the future, and indeed, her Musk mockery would prove prophetic. In the background of her painting, a mansion standing in for the old world order is on fire; in the foreground, a fast car promises both a getaway and an intimate interior, or a private reprieve. —E.W.

-

Carolyn Lazard, A Recipe for Disaster, 2018

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Trautwein Herleth, Berlin When Julia Child’s cooking show aired on TV, her network briefly experimented with open rather than closed captions, meaning they could not be turned on and off. Lazard, a disabled artist, picks up here, remixing an episode of Child’s show but taking its commitment to access one step further. Child already describes her actions, since the show is didactic. But where the captions fail to describe sound (only dialogue) and Child’s monologue neglects the scenery (only directions), Lazard fills in the gaps, looping in D/deaf and blind audiences. All this quickly accumulates into cacophony, which Lazard embraces. The crescendo, narrated by artist Constantina Zavitsanos, is a manifesto overlaying it all. Lazard revealed the limits of treating access as an afterthought; other artists—Zavitsanos among them—followed, making work that Geelia Ronkina dubbed “access materiality.” A movement was born, centered around works taking up captions, ramps, image descriptions, and so on as a medium—all recently chronicled in The Agency of Access, a book by art historian Amanda Cachia. —E.W.

-

Britta Marakatt-Labba, Historjá, 2003–07

Image Credit: Photo Hans-Olof Utsi/Courtesy Galleri Helle Knudsen, Stockholm For several centuries in the West, history painting was considered the highest form of art-making. Yet its scope was narrow, leaving so much history always overlooked. Artists like Marakatt-Labba revisited the genre in the 21st century, filling gaps by depicting histories that had not yet been told widely. Historjá is a 77-foot-long embroidered epic that translates the tradition into fiber, and ambitiously aims to depict the whole of the Sámi people’s history: their Nordic Indigenous lore, rituals, prosperity, and oppression rendered scene-by-scene via spare tableaux stitched into linen in a manner not unlike the canonical Bayeux tapestry. Refuting any narrative of progress that might posit modernism over Indigeneity, it begins and ends in a forest, whence the Sámi came. —A.G.

-

Tania Bruguera, Untitled (Havana, 2000), 2000

Image Credit: Denis Doorly/Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, York The 7th Havana Biennial, at which Tania Bruguera’s Untitled (Havana, 2000) debuted, invited artists to explore mass communication in the new millennium. But rather than a great connector, Bruguera framed communication as a tool for exploitation in Cuba. Bruguera’s work comprised fermenting sugarcane piled several inches high in a darkened tunnel in the Cabaña fortress, a military bunker once used to jail prisoners of conscience. At the end of the space was its sole illumination: a small television monitor suspended from the ceiling that played footage of Fidel Castro, who was still in power at the time. Only as they approached the monitor could visitors notice several nude male performers fiercely rubbing their hands together. The piece spoke to all that lay at the limits of vision in Cuba, a country whose repressive leadership has long tried to keep dissent out of sight, out of mind. Untitled (Havana, 2000) didn’t stay on view long—it was shut down by authorities hours after going up—but it was enough to spur on many dissident Cuban artists after Bruguera. —T.S.

-

Matthew Barney, Cremaster 3, 2002

Image Credit: Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York, Brussels, and Seoul Cremaster 3 is a strong candidate for the best movie ever about lamb-eating giants, balletically crashing cars, and Richard Serra flinging molten petroleum jelly inside one of our most august sanctuaries for the appreciation and narrativization of art. The longest feature film in a five-part cycle and the last to be released, the 3-hour fantasia plays as a sort of wordless cinematic tone poem filled with considerations of human evolution and reproduction (the “cremaster” muscle controls male testicles, and figures in the sexual differentiation of an embryo) and interconnected allusions to Matthew Barney’s expansive artistic universe. Starkly divergent vignettes vary from mysterious happenings within New York’s iconic Chrysler Building (the site of a surreal staging of six automobiles smashing into one another, over and over again) to an extravagant set piece in the Guggenheim Museum’s famous rotunda that features Busby Berkeley–style dancing, a hardcore-punk battle of the bands, and Barney himself climbing up and down the walls while interacting with a spectral woman who changes form into a cheetah. While it’s far from easy to apprehend, the film proves transfixing in its elusive and hyper-imaginative flights of fancy. —A.B.

-

Aliza Shvarts, Untitled [Senior Thesis], 2008

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist For an ambitious undergraduate senior thesis, Shvarts artificially inseminated herself each month for nine months—a routine she followed up with an herbal abortifacient. Her work highlighted the uncertainty that accompanies having a body, especially one that can become pregnant, and it drew attention to those womanly experiences that can be traumatic and ordinary at the same time. Each month, she would bleed heavily, not knowing whether the blood signaled a period, a miscarriage, or an early-stage abortion. Shvarts’s interventions lay bare the ways that bodies rub up against ideologies, existing in ways for which we often lack the language or knowledge to express. Or so argued Harvard art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty in her 2009 October article defending the young artist, who’d been subjected to vitriol, even death threats. —E.W.

-

Asad Raza, Diversion, 2022

Image Credit: Photo Diana Pfammatter For a show at Kunsthalle Portikus, located on a small island in Frankfurt, Germany, Raza rerouted the Main River so that it ran right through the museum. He didn’t stop there: inside, he filtered the water through a very fine coffee filter, then boiled it and added some minerals. Suddenly, the hydrologist-approved water was drinkable; guests were offered glasses of it. It was at once a mind-blowing feat and an extremely simple gesture. Beyond that, Diversion was galvanizing for the way it made survival and reconnecting with nature seem well within reach. —E.W.

-

Mendi & Keith Obadike, Blackness for Sale, 2001

Image Credit: Courtesy Mendi + Keith Obadike/Obadike Studio In 2001

,a shocking item appeared in eBay’s “Black Americana” category: an object that was labeled “Keith Obadike’s Blackness (Item #117601036).” It came with an opening bid of just $10 and a list of potential benefits and warnings, including one that read: “The Seller does not recommend that this Blackness be used in the process of making or selling ‘serious’ art.” In placing the work for sale on eBay, the Obadikes drew a connection between the history of enslavement, the auction block, and the website’s “Black Americana” category. The listing did not last long: eBay removed it after four days, by which point bidding had risen to $152.50. Yet Blackness for Sale has had a more enduring legacy, serving as an important intervention in the history of net.art, which had until then mostly avoided discussions about race. In doing so, the work prefigured later conversations around Blackness on the internet. —M.D. -

Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens), 2017

Image Credit: Mathias Voelzke The practice of quipu-making comes from pre-Columbian Peru, wherein various Andean peoples tied cords and colorful strands into knots to record events, information, and stories. For decades, Cecilia Vicuña has been making sculptural works that bring this age-old format into the present day, often with a feminist undercurrent. This work, one of the biggest pieces in the “Red Thread” series, was made for Documenta 14. Vicuña created 52 red wool strands, or chorros, and suspended them in a circular ring that hangs from the ceiling. The cascade of red fiber recalls the tenuous nature of life itself, bringing to mind flows of blood that result from wounds and menstruation; from certain angles, her wool forms even look like umbilical cords. Vicuña powerfully connects Indigenous modes of communication and feminine wisdom, suggesting that there are forms of knowledge that exist beyond history books and archives. —F.A.

-

Park McArthur, Ramps, 2010–14

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist For a formative show at Essex Street Gallery in New York (now Maxwell Graham), McArthur gathered 20 ramps, most of which had been improvised to accommodate the artist, a wheelchair user, during her visits to otherwise inaccessible art spaces between 2010 and 2013. The makeshift ramps were made of materials including plywood boards, a cupboard door, and handmade wedges. The show took place more than 20 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law, and highlighted both the inaccessible entrances that still punctuated McArthur’s every day and the caring improvisation that ensued. But it was more than an autobiographical show or a complaint about lack of compliance, with McArthur’s most crucial gesture easy to miss: Printed on one wall was the URL for the Wikipedia page McArthur built for Marta Russell, a disabled activist who wrote Beyond Ramps (1998), a book arguing that certain American economic policies are greater threats to the quality of disabled life than impairment itself. McArthur shined a spotlight on how disability is politically constructed, and a whole artistic movement took off in the wake. —E.W.

-

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015

Image Credit: ©Smoking Dogs Films/Courtesy Lisson Gallery Vertigo Sea seems to take place in the past, present, and future simultaneously, clocks ticking throughout the duration of this arresting three-screen video. Archival oceanic images of whales, seals, and enslaved people recur alongside newer shots of people in 19th-century European garb pondering cloud-covered landscapes. The soundtrack features quotations from the abolitionist Olaudah Equiano and novelist Herman Melville alongside other musings on the ocean, ranging from maritime disasters during the transatlantic slave trade to rising sea levels now and in the future. This haunted 48-minute installation can feel too intense to bear as interwoven historical strands accrete. Akomfrah presents history as an unstable narrative, filled with bits and pieces that get dispersed, reassembled, and reshaped in the wake of so much death and destruction. Conventional senses of time and chronology offer no aid in wading through the roiled waters of history. —A.G.

-

Delcy Morelos, El abrazo, 2023