The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore by Evan Friss. Viking, 416 pages.

My daughter and I were the only browsers in a small bookstore when a woman entered to ask how to find a nearby donut shop. “So I’m in the wrong place altogether,” she replied to the bookseller’s instructions. “Unless you’d like to buy a book,” said the bookseller. The woman laughed and left. Bookselling is tough; that’s nothing new. In Riceyman Steps, a 1923 novel, the proprietor of the eponymous bookstore and his wife die of impoverishment and immiseration. In The Private Papers of a Bankrupt Bookseller, a 1931 novel presented as a memoir, the destitute bibliophile gases himself. As novels, they present a dark fantasy of bookselling; and, maybe unsurprisingly, both are British. The bookstore in the American imagination—established in part by Christopher Morley’s The Haunted Bookshop (1919), where customers receive bibliotherapy amid the lamplit labyrinth of a “warm and comfortable obscurity”—is a happier place. As scholars Kristen Doyle Highland and Eben Muse have demonstrated, ours is a fantasy of homey nooks where contingency and serendipity rule, outside the dictates of worldly time.

Evan Friss announces his commitment to this fantasy with the title of his new book, The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore. Typically, bookstore is American usage and bookshop is British. But the booksellers at Friss’s paragon, Three Lives & Company in Greenwich Village, think store “sounds too commercial” and prefer shop—so he does too. Three Lives is a place where life happens. Camille remembers to ask after your ailing grandmother; Richie pops in with a “wedge of Gruyére”; Adrienne drops off ballet tickets she can’t use. And fair, if Friss is a little biased: his wife worked there for eight years. A rheumatologist, “Dr. Gary,” once diagnosed her with shingles among the shelves. The novelist David Markson flirted with her, called her the “girl of my dreams.”

Bookselling is tough; that’s nothing new.

Three Lives is an odd place to start a history of bookselling in the United States. It is, as Friss acknowledges, an anomaly. “Conventional wisdom suggests that for bookstores to survive, they need to sell heaps of sidelines (higher-margin nonbook merchandise), host near-daily events, maximize social media, and leverage technology.” Three Lives does none of this. It is, as it advertises on its website—it has a website, even if looks like it was designed in 2004—an anachronism. How, then, does it persist?

Friss asserts that its “simplicity is its brilliance. The tiny bookstore is filled with books and books and books and books”—just books! “It has charm, personality, and soul.” We should all be so lucky to have our own Three Lives in our neighborhood. But we can’t, and not because our local booksellers haven’t considered simplicity, or lack charm. Three Lives has “unusually affluent and well-educated” neighbors, including NYU students, but I wondered if even that was enough. I wrote to the store to ask about its finances but received no reply. Its owner’s brother is a world-famous garden designer and widower of “Pierre Bergé, the pugnacious business brain behind the original Yves Saint Laurent fashion empire,” according to a 2017 New York Times profile. The owner’s mother, I learned from her obituary, was “a patron to numerous charitable organizations.”

The Bookshop’s thirteen chapters profile thirteen types, usually choosing one as an exemplar. Friss gives us department stores (Marshall Field & Company), gay bookstores (Oscar Wilde), black bookstores (Drum & Spear), superstores (Barnes & Noble), internet booksellers (Amazon), even Nazi bookstores (the Aryan Book Store). Some of these could be called bookshops; others, not so much. In between, we get brief interludes showcasing bookstore fixtures (The Smell, The Cat, The Kids, The Guy Who Never Buys Anything, The Weirdo). Friss moves chronologically, from Benjamin Franklin’s New Printing-Office to Ann Patchett’s Parnassus. He draws on archives, interviews, primary documents, and previous scholarship—though because this is Big Five trade nonfiction, the scholarly apparatus is quietly tucked away in back. He can be funny if you like dad jokes. (I do.) An academic by trade whose first two books are histories of the bicycle, he is sometimes twee. As a fan of bicycles, Belle and Sebastian, and Wes Anderson, I mean this kindly.

Stylistically, Friss adopts close third-person perspective and sometimes slips into free indirect discourse, a technique by which a narrator expresses the thoughts of a character. Each chapter, that is, takes on something of the bookseller’s point of view. In Friss’s hands, this is an empathetic mode of narration; he feels with the Gotham Book Mart and the Strand. But such ventriloquism makes it challenging at times to suss out what Friss really thinks: Is he expressing his position or the store’s? There are two exceptions: Amazon and the Nazis. He dislikes both and make this clear by adopting a more distant tone.

The result is an immersive, character-driven series of episodes that forgoes a unifying argument. Though chronological, it doesn’t do the synthetic work to explain how bookstores have changed over time. It is particularist, not systematic.

He is less interested in investigating how bookstores might survive than in asking: How should a bookshop be?

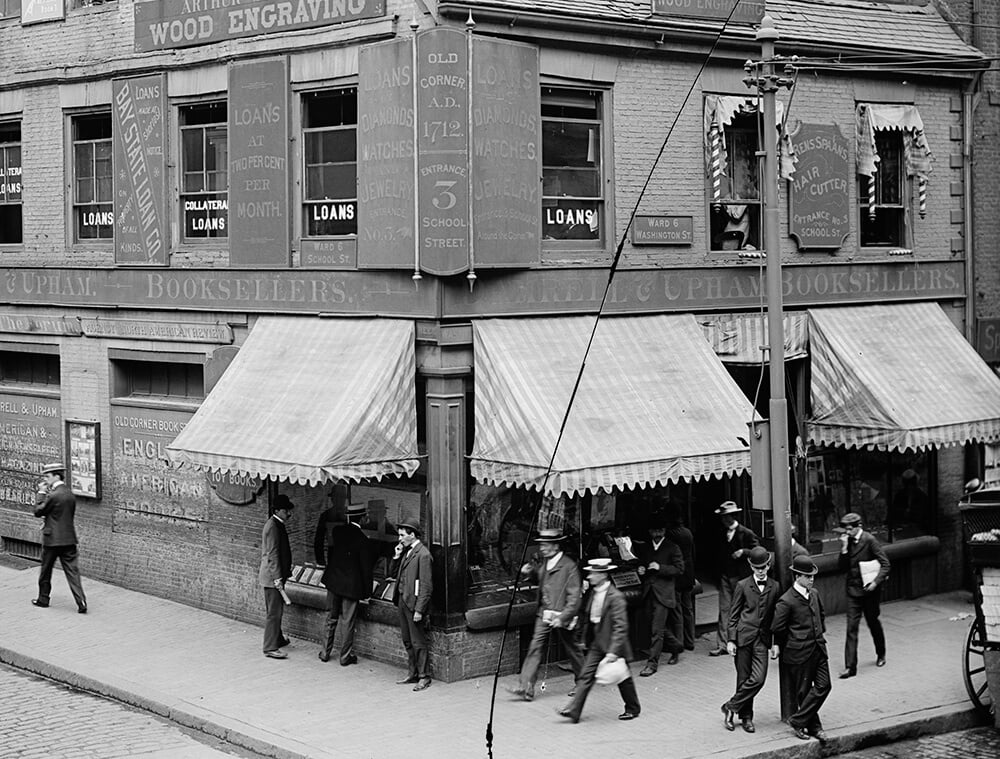

The individual episodes are compelling. They brim with telling details: Benjamin Franklin among “fat kegs of ink, cases of type (he used Caslon but preferred Baskerville), reams of paper, pages dangling from the ceiling to dry, and heaps of rags,” at a time when bookstore wasn’t yet a word and The New Printing-Office was a printer, post office, and paper seller that also sold some books. We leap from the eighteenth century to the nineteenth century with The Old Corner, run by a young William D. Ticknor and an even younger James T. Fields. There was a very small market for books: “few people read for leisure.” In 1832, “there were only 1,553 American-published books in print.” But these two fledgling booksellers became the publisher Ticknor and Fields, and out of The Old Corner they published Lydia Maria Child, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Atlantic Monthly, and Tick’s close friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote in the store. They turned down Little Women: Fields told Louisa May Alcott to stick to teaching.

And on it goes. By the fourth chapter we’re squarely in the twentieth century with Field’s, the epic Chicago department store, which had “68 elevators, 127,000 feet of pneumatic tubing, thousands of employees, and 700 horses standing by for delivery,” along with its “Czarina” of books, Marcella Hahner, a tiny woman with outsize influence on the literary field. The portrait of Hahner and Gotham Book Mart’s Frances Steloff—who, among much else, held a wake for the launch of Finnegans Wake and sold contraband books from beneath the counter, such as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer to future Grove Press impresario Barney Rosset—are among The Bookshop’s most memorable.

He might evade argument, but Friss leaves crumbs that lead us to one. He is less interested in investigating how bookstores might survive than in asking: How should a bookshop be? In the dead center of his book, Friss reveals a commitment to evenhandedness that, under light pressure, becomes the sinister proclivity for false equivalences of the well-meaning liberal.

Friss reminds readers that, from the colonial period through the present, bookbuying, especially at bookstores, has been the province of “the well-educated and the upper classes.” But as sociologist Laura J. Miller argues in her classic study of American bookselling, Reluctant Capitalists, in the twentieth century, innovations in the trade expanded the classes of people who might buy books. Starting in the 1920s, the Book-of-the-Month Club made literature more accessible to the middle class. When Pocket Books created the modern mass-market format in 1939, it made literature into mass culture—even if you were unlikely to find the small, cheaply made books in most bookstores, intimidating places known to judge a customer’s taste and recommend toward moral uplift.

When chain bookstores like B. Dalton and Waldenbooks proliferated in suburban malls in the 1970s, they transformed the culture of bookselling again, argues Miller. Rather than dark, stuffy spaces where a bookseller might offer an unsolicited suggestion, shoppers could enter bright, clean, spacious stores that felt like any other retail outlet in the mall. A democratizing ethos prevailed: consumers should choose what to read for themselves. The chains used computers to track and analyze consumer data and to stock shelves accordingly. In the 1990s, the superstores, Barnes & Noble and Borders, supplanted the mall chains; they were bigger, they had cushy armchairs, they had cafés, they sold bestsellers at deep discounts, all of this inviting us to linger, which I did in my early twenties, reading Harper’s cover to cover or studying for the GRE without buying the book.

The market, that is, came for bookselling like it did for everything else. And out of this neoliberal transformation came the indie bookstore, a term whose currency, as Friss explains in his final chapter, begins in the twenty-first century. The chains and superstores were bad for bookstores, but the apotheosis of the market, the queen of rationalization—Amazon—was apocalyptic. In the late 1990s, bookstores began going out of business at unprecedented speed. To staunch the bleeding, the American Booksellers Association (ABA) built PR campaigns that branded non-chain, non-superstore, non-Amazon bookstores as indies. At the same time, to survive, the newly christened indies were adopting techniques developed by their predators to juice revenue: cafés; computerized accounting and stocking; events; sidelines; welcoming spaces. They offer recommendations but only within the democratized ethos where the customer is always right. All of this is packaged as part of a political commitment, “signaling,” as Friss writes, “a set of values: supporting communities, small businesses, and maybe even the cultures of reading and democracy.” The indie bookstore is a dialectical synthesis of the crusty old bookstore and the rationalized superstore.

You won’t find language like this in The Bookshop. The book expresses a liberal centrism—consider the capacious pluralism of Friss’s close third style—and Friss is an idealist, not a materialist: if he has a position he advocates, it’s that books and the ideas they hold can change the world for the better.

Books can change the world; let the customer decide which ones.

But he won’t say which ideas. This is in line with the contemporary ideology of bookselling, per Miller: “The bookseller’s power to do good comes from the ability to expose people to new ideas. But what this bookseller refrains from doing is specifying which of those ideas are more deserving than others.” Most revealing is where this ideology hits its limits. Friss implicitly endorses when booksellers dismiss lowbrow literature: Iceberg Slim, Danielle Steel, pornography, smut. He also, as noted, rejects Nazism—but the type of bookstore exemplified by the Aryan Book Store in the seventh chapter, at the heart of The Bookshop, isn’t the Nazi bookstore. It’s the “radical bookstore.” And the chapter is equally devoted to the communist bookstores of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Friss writes, “Radical bookstores took many forms and often served as part of larger, multichannel campaigns. Nazis, as well as Communists and Socialists, organized festivals and parades, dances and concerts, and schools and camps to disseminate critiques of American democracy and American capitalism.” No matter that he goes on to treat communism with more tolerance than Nazism: the false equivalence has been established by the structure of the chapter. The final paragraph—which calls Amazon “the new radical bookstore” where, say, white supremacists can now buy their books—seals it.

Late in the chapter, he makes another false equivalence while engaging debates over bookstore curation and book banning in the 2020s. Beyond Amazon, today’s radical booksellers look like Josh Cook of Porter Square Books in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who, writes Friss, “called for greater efforts to rid bookstores of harmful books” from the position of the left. “Conservatives made the same argument,” writes Friss, “albeit with a different definition of ‘harmful.’ School superintendents, teachers, parents, librarians, journalists, state legislators, and booksellers went to war over books, trying to ban certain titles or promote those very books being banned.” This is the nadir in The Bookshop’s already most compromised section, a misrepresentation of Cook’s argument and a disavowal of the basic logic of bookstore curation.

Cook’s The Least We Can Do: White Supremacy, Free Speech, and Independent Bookstores, was originally published as a chapbook in 2021 and reprinted in The Art of Libromancy, a collection of essays, in 2023. Elsewhere in the collection, Cook distinguishes between what he calls conservative and progressive bookselling. The conservative bookseller, an imagined archetype at one end of a spectrum, is fully rationalized and committed to market democracy. Curation “is almost entirely a sales-prediction skill.” Fill your shelves with what your customers are most likely to buy. The progressive bookseller intervenes with his own judgment, choosing his stock to resist, say, the white supremacy of Trumpian politics, or to push back against the disproportionate power of the Big Five publishers by selecting and foregrounding work from small presses. The customer might believe they make their choices freely, but the massive mechanisms of the publishing industry, with its deeply embedded inequities, have placed a heavy hand on the scale. Cook’s progressive bookseller, the alternative archetype, is conscious of the role bookstores play in that system and makes choices to challenge the status quo and to invite customers to discover books they might not have found without such an intervention.

As Friss knows, every bookstore only stocks a tiny percentage of all books, so each one requires saying no to countless others. In The Least We Can Do, Cook argues for refusing to stock work by Republican politicians: leave books by Mike Pence off the shelf out of consideration for one’s queer customers. In conversation with Publishers Weekly, he said, “I don’t argue for not selling certain books—I argue for not stocking them.” If a customer asks for Pence by special order, go ahead. Obviously, Cook’s argument is entirely different from the conservative project to ban books in public libraries and schools, and Friss is disingenuous when equating them. It’s too bad because the Nazi material on its own is fascinating. The Aryan Book Store had “an air-rifle shooting range on the mezzanine.” Its manager, Hans Diebel, would hang out there and pretend “to hunt down Jews.”

But the problems with the chapter are salutary insofar as they clarify Friss’s commitments. Books can change the world; let the customer decide which ones. Just not lowbrow trash or radical work that undermines society. Go with respectable literature, liberal multiculturalism, and mainstream politics inclusive of Trump.

I love bookstores. I visited many during the months that I worked on this essay in the Twin Cities and in Atlanta. At The Irreverent Bookworm, a queer bookstore in Minneapolis, I was handsold 84, Charing Cross Rd, and told it was required reading for new hires: a record of the correspondence between an acerbic American writer and a sweet British antiquarian bookseller. It’s also, it turns out, Friss’s favorite book about booksellers, and he’s not wrong. I picked up Kate Briggs’s The Long Form and Emily Hall’s The Longcut at Magers & Quinn. Across the river in St. Paul, I found on the shelves at Midway Used & Rare Books a copy of Percival Everett’s debut, Suder, reprinted by LSU Press, signed and inscribed to Patrick, whom Everett met at Middlebury’s Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.

Bookstores are places that can interrupt the flow of publishing’s culture industry by showcasing books that customers might not otherwise see.

Bookstores are struggling. We might say The Bookshop is the story of a rise and fall. Friss offers a bleak analysis in his final pages, explaining how the vaunted indie comeback of the last few years depends on misleading data from the ABA. According to the U.S. Census, “between 2012 and 2021, the number of bookstores dropped by 34 percent.” Not much of a comeback, though there is some disagreement on this point. Larry Law of the Great Lakes Independent Booksellers Association reported to me that when he began as director in 2018, the organization had about 130 member stores and that today it has about 350, without counting questionable bookstores such as Hudson News or other large chains. “We have definitely seen a boom in growth,” he wrote. “We’ve been up every year since 2018. Growth peaked during the pandemic (2020, 2021) and growth has since leveled out.” Maybe the Great Lakes region is an anomaly, or maybe the story is more complex than either the data from the ABA or the U.S. Census allows.

Still, going by the national numbers—whether from the ABA or the Census—we have fewer than half the bookstores we did in the mid-1990s. To stay in business, it helps to be independently wealthy or a famous author, not that Friss is clear about this. One of his interludes celebrates RJ Julia, an indie bookstore in Connecticut. “RJ Julia,” he writes, “is now one of those famed indie bookstores that has lasted for decades, outliving many of the forces that once threatened to destroy it.” Though he notes that its owner, Roxanne J. Coady, left “behind a partnership in an accounting firm,” he elides that it was BDO Seidman, one of the top ten accounting firms in the United States, and that she was its first female national tax director; he elides, too, that her husband, Kevin, is a real estate developer with a reputation for marinas.

For Friss, the ideal bookstore is an anachronistic haven, a retreat from the hurry of contemporary life, a place where neighbors know each other, where one might browse while hearing the soft clicks of a rolling ladder. It’s a popular fantasy. Bookstores are places, too, that can interrupt the flow of publishing’s culture industry by showcasing books that customers might not otherwise see. The art of handselling is a beautiful thing. And booksellers talk to each other. If one champions a book that would otherwise disappear, a few others might, too, and then a few others. It happens all the time.

As I was finishing this review I went to my preferred local bookstore, A Cappella in Atlanta, to pick up Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob. Several titles were prominently displayed at the register. One was The Bookshop.