In Chantal Akerman’s film La Captive (2000), a loose adaptation of the fifth volume of Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time published in 1923, a young man named Simon attempts to psychically capture his lover to no avail. Tracking her whereabouts at all times cannot console his insatiable and impossible desire to know her in total.

In her new book-length essay on the film, from which it takes its name, Christine Smallwood similarly explores such a rapacious obsession — not just for the controlling, voyeuristic character of Simon, but for the critic herself, as well. “Criticism, like dreams, often involves some act of displacement, in which the writer transfers feeling from her own life to the object, or in which one object substitutes for another,” she writes in her introduction. Here, Smallwood underscores the central theme of her book: the fact that we invariably bring our personal histories to bear on an obsession or object of inquiry, and often turn our gaze inward to watch ourselves doing so.

Part close reading, part portraiture of Akerman, Proust, and herself, Smallwood’s engrossing essay traverses notions of time, transference, and captivity and was written during the COVID-19 pandemic while caring for two small children. Smallwood grounds her writing in her visceral reaction to Akerman’s sentiment “that duration itself can be art.” Akerman said of her films, “What I want is to make people feel the passing of time. So I don’t take two hours from their life. They experience them.” But for the critic, especially one with small children confined to the home, time is a scarce luxury. To experience two hours of a film is to miss two hours with a child, a partner, or a parent. In one of several moments in which she interrupts the text to comment on the writing process itself, Smallwood explains that “writing this essay feels less like shaping time than pouring it into the sink.” While writing, her baby grows up. Time passes, irrevocable and lost. It is therefore inevitable that Smallwood’s experiences as a mother mid-pandemic inform her analysis of Akerman’s film.

To wit, when Simon humps Ariane before instructing her to go back to sleep, Smallwood acknowledges the pathology of this interaction while once again projecting her own feelings onto an objectively disturbing scene of abuse. The sleep-deprived critic, a captive in her own home, cannot help but read Simon’s controlling directives as “a beautiful fantasy about true domestic harmony.” Sometimes we study a text so closely that we see past the violence right in front of us: Smallwood’s reading (or misreading) is deeply imbricated in a personal desire and need. There is no objective analysis.

Perhaps what allows Smallwood to insert her own life into the analysis of La Captive is Akerman’s style and form. Famous for her frontal shots and long takes, Smallwood quotes Akerman as having once said, “When you film frontally, you put two souls face to face equally, you carve out a real place for the viewer.” Akerman’s surfeit of durational shots allows for drift, wherein the viewer can infuse these moments with their own life and inner thoughts. If, as she writes, a “lack of reserve shots displace the reaction onto the audience” in Akerman’s film, Smallwood deftly performs this displaced reaction in her prose. The result is a compelling close reading of what it means to be captivated and captured: by art, by time, by children, and by all the other everyday detritus that constitutes a writer’s and mother’s life.

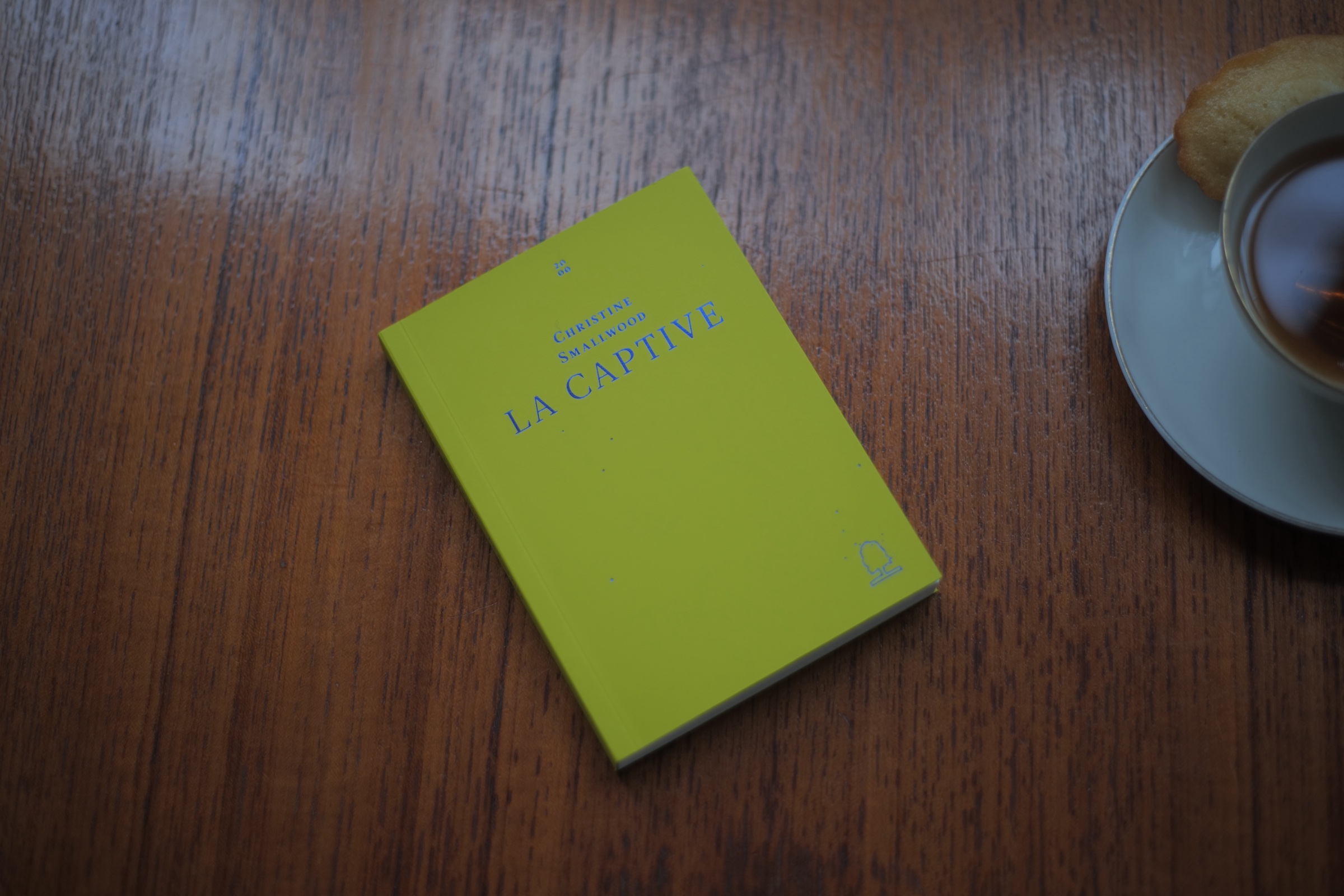

La Captive (2024) by Christine Smallwood is published by Fireflies Press and is available online and through independent booksellers.