Early this summer I was interviewed by Rose Horowitch, an editor for The Atlantic. She told me that she had heard from a university professor that incoming students were struggling to keep up with the reading load. She explained that she was working on an article that would explore the problem of reading stamina and asked me to share my experiences in the high school classroom. I was not surprised by Horowitch’s hypothesis. She attributes undergrads’ lack of reading stamina to lowered expectations in high school literature curricula, specifically arguing that limiting full-length novels and replacing long-form content with excerpts and summaries has weakened readers’ constitutions. She, in turn, ascribes these instructional choices to the oppressive presence of standardized testing and the Common Core. And cell phones, always cell phones.

It is a perfectly reasonable assumption, but it’s wrong. This is not to say that there aren’t external factors affecting students’ reading stamina, but to line up such a simple series of dominoes to topple oversimplifies a complex challenge and places undue blame on the shoulders of discerning young readers and the public school teachers who work tirelessly to support them.

My primary concern throughout the summer of interviews, emails, and fact-checking, was that we were slipping into a familiar panic in the face of progress: how will this next technological or social development bring about the downfall of society? It’s an old story; in the fall of 1978, The MATCY Journal published a handful of “probable” quotes from history including the infamous lament over the proliferation of paper: “Students today depend on paper too much. They don’t know how to write on a slate without getting chalk dust all over themselves. They can’t clean a slate properly. What will they do when they run out of paper?” This, and the other quotes in the article, aren’t actually real. However, they reveal a genuine pattern in panicked thinking that, rather than unveiling flaws in social and technological change, instead lays bare the atrophied mindset of the people doing the panicking.

From a similarly stodgy perspective, Horowitch’s article reflects a frighteningly narrow definition of what constitutes worthwhile literature. Passing references to Moby Dick, Crime and Punishment, and even my unit about The Odyssey, confine literary merit to a very small, very old, very white, and very male box. As a staunch advocate for diverse and representative literature, I was immediately curious about the actual texts at the center of this “crisis” so I asked Horowitch directly what types of books were the sticking points in her professor friends’ curricula. Unsurprisingly, it was canonical classics. As Horowitch points out, I am just “one public-high school teacher in Illinois,” but while professors at elite universities sound the alarm over Gen Z undergrads not finishing Les Miserables because they are uninterested in reading a pompous French man drone on for chapters about the Paris sewer system, my colleagues and I have developed professional toolboxes with endless other ways to inspire our students to read about justice, compassion, and redemption.

And that’s a good thing, since Gen Z and Gen Alpha don’t cow to authority for authority’s sake. They simply won’t do things they don’t want to do, and I actually kinda love that. The rising young generations want texts that matter to them, that reflect their lives and experiences. So when we force-feed yet another vanilla canonical dust collector, and then complain that they aren’t playing along, it’s just not a good look for us.

Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone, Ibi Zoboi’s American Street, and David Bowles’s The Prince and the Coyote, are all complex, challenging, and substantial texts that speak to the interests and experiences of my students, so it’s not a fight to get them reading. Frustratingly, despite the numerous examples I provided of students reading books cover-to-cover in my class, Horowitch opted to include only the unit that, like the original rhapsodes of the bronze age, I excerpt and abridge. Equally frustrating is that her article implies that I was forced into that decision in order to pacify floundering students or submit to the demands of standardized testing.

Rather, my experience is that young readers are eminently capable of critically engaging in long form content, but they’re rightfully demanding a seat at the table where decisions about texts are being made. Luckily, we are living through a literary renaissance. Publishers are flourishing amid a profusion of stories, books that give voice to the experiences of people who look and live like the young readers in my classroom. There is no shortage of engaging texts that students can and will read cover-to-cover. But if we insist that quality literature must come from old dead white men, we are consigning ourselves to irrelevance before we even begin.

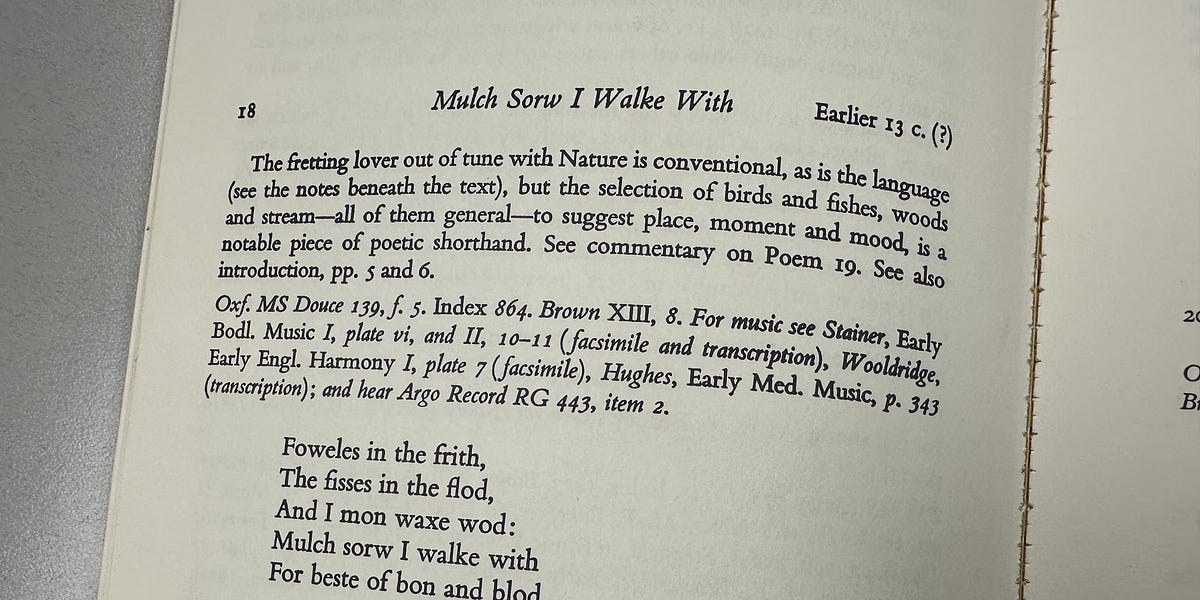

One often overlooked hurdle that I brought up with Horowitch was the impact of language evolution on reading comprehension and comfort. Linguistically, the dialect of English spoken by contemporary adolescents is rapidly moving further away from the vernacular of the canonical works we ask them to read. While this has always been true to some degree, social media and technology have sped up language evolution and widened the gap between English dialects. My students code switch into my spoken dialect to engage with me -something that I never had to do to communicate with my teachers in high school. So when I ask them to shift further into the recesses of linguistic history to read Shakespeare, the struggle is real. The additional layer of linguistic distance between them and Shakespeare remind me of my own struggles through Chaucer in the original Middle English -difficult and worthwhile, but truly a challenge. As a society, we have become more accepting of vernacular differences and demand less code switching -all good and important changes that validate students’ identities. But it does inevitably become harder to successfully navigate long form texts in dialects of English that are fading ever further into history. As a responsible educator, I require more justification than merely longstanding tradition as I set a course for my precious minutes in the classroom.

One of the reasons I have found so much success with The Odyssey, aside from the monsters and murder, is that the emerging generation of translators, including Dr. Emily Wilson and Maria Dahvana Headley have been transparent about their processes of bringing new life to canonical treasures like The Odyssey and Beowulf. In one lecture, Wilson explains that historically, translators intentionally archaized their language to establish gravity and reverence for these works, a tradition the new generation of translators are choosing to break from because of the exclusionary effect it has on readers. Contemporary translators have shifted their mindset from one of preserving tradition, to one of illuminating narrative and purpose. Homer wanted his audiences to be both entertained and shepherded into the culture. Wilson wants that too, and so she gives us a deeply relatable, heartbreakingly honest, and eminently readable translation of The Odyssey. In allowing her understanding of the story to shift with time, she remains truer to the story’s original purpose and relevant to a new generation of readers.

These are all points I made in speaking to and emailing with Horowitch and her fact checkers throughout the summer. I have to think, I was not the source she was hoping for. I was a problem. Perhaps the most disappointing defeat I observed in the final article was that although I shared my observations of the tireless work of colleagues at the state and national level advocating for intellectual freedom, Horowitch does not acknowledge that culturally, we do not value reading. We ban books, scrutinize classroom libraries, demonize librarians, and demoralize teachers. We pay lip service to the importance of literacy, requiring four years of English and regularly testing literacy skills, but when push comes to shove, we don’t make space for the curiosity and joy that are the foundations of lifelong literacy habits. In truth, we seem to be doggedly fighting against the best interest of a literate populace. While aggressive censorship is an agony I’ve been spared in my current position, it is a formidable obstacle I see my colleagues and heroes across the state and across the country struggling with.

Instead, Horowitch places heavy blame on standardized testing and the Common Core. I argue that this blame is misplaced and irrelevant. While there is absolutely a push for analytical skills to be developed (see AP curriculum and testing), truth be told, Common Core or College Readiness, they’re more similar than different. The pressure to switch from one set of standards to another isn’t much more than a nuisance in the grand scheme of teaching. In practice, teachers have always balanced various standards and testing with a familiar degree of disruption to the important work of building practical literacy skills. The never-ending cycle of new initiatives and projects outlasted by tough-as-nails veteran teachers is the oldest trope in the faculty lounge and certainly not newsworthy enough to merit The Atlantic’s hefty subscription fee.

In a move as cliché as blaming standardized testing, Horowitch takes aim at smartphones and social media, a constant classroom annoyance to be sure, but old news, at least among high school educators, who have already read The Anxious Generation, adapted our routines, and moved on. It seems too easy of a target to take seriously in the context of a major American journal like The Atlantic, but here we are. It should go without saying that there is a medium between TikTok and Tolstoy. If we position ourselves as fighting against social media and short-form entertainment, we’ve already lost. The dopamine hit from the ding of a push notification is far more neurologically satiating than anything I have to offer in a classroom. So even as I continue to develop more engaging curricula, I ask my students and their caregivers to reframe their expectations, to reconsider the type of “entertainment” that they expect from my class. When my students shift their mindset to enter my classroom expecting nerdery, thought-provoking conversation, and midwest dad jokes, they find that the forty-five minutes passes enjoyably. I trust the literature because I am confident in my skill as an educator.

Creating space for the joy and curiosity of reading is important work that high school teachers step up to every day, designing lessons to teach what once came naturally. Previous generations turned to reading as a leisure activity, so they had an innate sense for how to read in school and how to read sneakily under the covers way past bedtime. To some degree, all of the things I’ve mentioned in this essay have stripped reading of its human value and made it into a chore. Teachers are thus charged with retraining kids to love books. It’s hard, but it’s working. Again, the current proliferation of complex and substantial young adult texts is a goldmine -if we don’t cut off access. But we have to be intentional about teaching young people how to read for fun versus how to read for academic purposes, and it’s not something that all professors have been trained to do. At the secondary level, we differentiate between the short works that must be read closely and copiously annotated versus the more substantial works that must be comprehended and revisited, pondered and discussed in a social-academic collaboration. Are the panicked professors expecting -or implying- that their students should be giving everything the close-reading treatment? Are the professors clearly communicating appropriate expectations? In my sophomore honors class, I invest time in teaching my students how to build their understanding over several readings of a scene, chapter, or poem at various degrees of scrutiny and analysis, and that is an investment I consistently see returns on.

The golden rule of maintaining a presence on social media is to stay clear of the comment section, but realistically, its siren song is impossible to resist. In this case, I truly wish I had tied myself to the mast. The Atlantic’s promotional tweet for this article quickly ignited a barrage of ill-informed comments about the “dumbing down of the American education system” and gratitude for yet another reason to homeschool or unschool or outschool. It’s a familiar cadence for those of us who have devoted our professional lives to education, and still try to maintain an online existence. While this essay is evidence enough of my frustration, I’m first and foremost an educator. I accept The Atlantic’s journalistic tantrum with a grain of salt, understanding that its articles are unbearably long and perhaps this topic cut the author a little close to the bone. I can extend my compassion and pity, but then I have to get back to work -we’re starting The Odyssey tomorrow and I have some eyeball puns to sharpen before we hit chapter nine.

Gratitude to my forever editor, Blake “The Hammer” Thomas.